History of the American School 1882-1942 - Chapter IV

A History of the American School of Classical Studies, 1882-1942

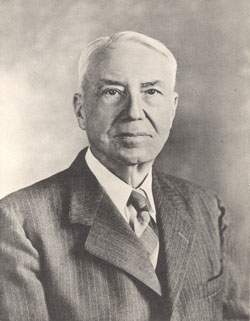

Chapter IV: The Chairmanship of Edward Capps of Princeton University, 1918–1939

Edward Capps was graduated from Illinois College in 1887. He received his doctor’s degree from Yale in 1891. He had already been appointed Tutor in Latin at Yale in 1890 and two years later had the distinction of being invited to join that remarkable group of teachers whom President Harper gathered about him to build the newly founded University of Chicago. There he taught and wrote, edited the twenty-nine volumes of the University’s Decennial Publications, founded and edited Classical Philology. He lectured at Harvard on the Greek theater and was Trumbull Lecturer on Poetry at Johns Hopkins. He was called to Princeton as Professor of Greek in 1907. He had studied at the School when White was Annual Professor, and his work on the Greek theater and on Menander had given him a recognized place among the authorities on the Greek theater and the Attic drama.

Capps’s chairmanship began with an interregnum. When Wheeler died, February 9, 1918, the Executive Committee, consisting of Horatio M. Reynolds, Allen Curtis, James C. Egbert, Paul V. C. Baur, George E. Howe, Edward Capps and Alice Walton, at once asked Professor Edward D. Perry, of Columbia, to serve as Acting Chairman. At a meeting in New York, March 28, 1918, he appointed a committee to report at the annual meeting in May on the advisability of electing a permanent chairman at once or, in view of the conditions created by the war, postponing such a choice and carrying forward the affairs of the School under the direction of an acting chairman. This committee was also instructed to present a nomination in accordance with its recommendation. The committee appointed to make this important decision consisted of Perry, Curtis and Howe of the Executive Committee, and from the Managing Committee at large Allinson, Bassett, Fowler and Smyth.

Reporting unanimously May 11, 1918, the committee recommended the election of a permanent chairman and nominated Edward Capps. His election was immediate and unanimous.

Professor Capps’s engagements prevented him from assuming the duties of the chairman at once, and it was agreed that he should assume office on September 1, 1918. Perry was continued as Acting Chairman till that time.

During the summer, however, it was decided that a Red Cross Commission should be sent to Greece. Capps was asked to act as director with the rank of lieutenant colonel, and Henry B. Dewing was attached to his immediate staff with the rank of captain. Capps at once offered to resign the chairmanship of the Managing Committee, but the Executive Committee urged him to retain it, offering to continue the arrangement by which Perry served as Acting Chairman till Capps should be free to return to America. Fortunately for the School, Capps consented to these conditions. He actually assumed the chairmanship on December 1, 1919.

At the same meeting at which the Executive Committee had successfully urged Capps to retain the chairmanship, they had also voted to ask the Trustees to put the School property and the School personnel at the disposal of the American Red Cross. This the Trustees consented to do.

Accordingly Capps, on behalf of the Red Cross Commission, and Hill, on behalf of the School, arranged that the School building should be rented by the Red Cross for their headquarters. The staff of the Commission were accommodated in the student rooms of the upper floor and two rooms on the ground floor. This meant that the building was occupied continuously during the two years while the School was inactive (1918–1920) and that the School received a moderate compensation for the use of the building and the rent of the rooms. The building was (so the acting chairman thought) “subjected to unusual wear and tear” during its use by the Commission, but the Red Cross made a small grant to compensate for this. In addition, the members of Capps’s staff added many items of furniture to the rooms they occupied—articles which, in departing, they left behind them for the comfort of future students. Though the cost of repairs to the building at the close of its occupation” amounted to twenty-seven hundred dollars, by the arrangement the School had not only benefited from a financial point of view but had rendered a patriotic service which was not forgotten.

The Commission’s staff became much interested in the work of the School and established a Red Cross Excavation Fund. Among the first subscribers were Lieutenant Colonel Capps, Major Alfred F. James, of Milwaukee, Major Horace S. Oakley, of Chicago (later a Trustee of the School), Major A. Winsor Weld, of Boston (later a Trustee and Treasurer of the School) and Major Carl E. Black, of Jacksonville, Illinois. This fund amounted eventually to $3,034.57.

The Red Cross and the School also cooperated in securing a wholesome water supply for Old Corinth. The School provided the labor, and the Red Cross supervised the sanitation.

It has been noted that much difficulty arose in the excavations of Peirene from the fact that this fountain still supplied water to the village of Old Corinth. During the winter of 1919 heavy rains had brought down from the hills so much mud that the drains had been clogged, and the stagnant water accumulating in the excavations had become a breeding ground for malarial mosquitoes. The Red Cross joined the Greek Archaeological Society, the village and the American School in remedying this situation. The drains were cleaned, and pipes were laid, carrying Peirene’s waters to the village and restoring normal conditions. The Greek Archaeological Society contributed eight thousand drachmae, and the village gave the labor of two hundred men for a day and the entire cash balance in the village treasury, two hundred drachmae. These sanitary rearrangements were supervised by Hill.

During these two years there were no students in residence. The staff of the School consisted of the director, B. H. Hill; the secretary, Carl W. Blegen; the architect of the School, William B. Dinsmoor; and during the second year (1919–1920) Henry B. Dewing, who had been promoted to the rank of major in the Red Cross and who was appointed to the annual professorship in May, 1919. They all rendered conspicuous service to the Red Cross.

Hill took charge of the Home Service Bureau, where his chief duty was to see that allotment checks and insurance certificates for the twenty-five thousand-odd Greek soldiers in the American Army reached their proper destinations in Greece. Later he assisted efficiently in the anti-typhus campaign in eastern Macedonia and Bulgaria. Blegen organized relief work among villages near Mount Pangaeon and at Drama. He also inspected for the Red Cross concentration camps in Bulgaria and reported on conditions in western Macedonia and northern Epirus.

Dinsmoor was given a lieutenant’s commission in the United States Army in August, 1918, and assigned to duty as a military aide to the American Legation in Athens. In April and May, 1919, he found time to add further to his knowledge of the Propylaea area by excavations in the southwest wing. This excavation gave important evidence regarding the foundation of the early Propylon.

The Greek Government expressed its appreciation of the service of the School staff to the Greek nation by conferring on them distinguished decorations. Capps received the Gold Cross of a Commander of the Order of the Redeemer (the highest order of Greek chivalry) and the Order of Military Merit of the Second Class with Silver Palm; Hill and Blegen received the Gold Cross of an Officer of the Order of the Redeemer. Dewing also received this decoration and in addition the Order of Military Merit, and Dinsmoor was given the Order of Military Merit of the Fourth Class.

This is not the place to speak of Capps’s administration as Commissioner of the Red Cross to Greece. It was characterized by his usual clarity of vision and all-pervasive energy. As an Associate Director of Personnel in charge of the New York Branch of the National Headquarters I had reason to know this personally. The first official communication I received from him was a cable directing me to impound a certain chiropractor in the service of the Red Cross who was returning from Greece and relieve him of a Greek decoration which he had fraudulently obtained.

Capps presented his first report to the Trustees for the year ending August 31, 1920. It is a remarkable document. Clearly a new, vitalizing force was at work in the Managing Committee.

The report not only surveys the condition of the School at the close of the war and lays down the program for the resumption of work but makes a number of concise suggestions for the future and announces a plan of action. It is worth while to summarize this report and to see, in anticipation, how many of these proposed objectives were realized.

Capps at the beginning of this report paid a well deserved tribute to the wisdom of the founders of the School, who had been so careful to separate the functions of the Trustees from the functions of the Managing Committee:

The above recital of our relations with the Cooperating Institutions shows a most gratifying spirit on the part of their representatives on the Committee, and bears testimony to the wisdom of the policy which was adopted when the School was founded and has been tenaciously adhered to throughout the forty years of its existence. I refer to the plan of management which makes the elected representatives of the colleges and universities which contribute to its support the governing body of the School. The Trustees of the School are the custodians of its property and funds; but the income derived from the several sources is placed without restriction at the disposition of the Managing Committee, which makes the budget and directs the internal affairs of the School, electing as its administrative agents a Chairman and an Executive Committee. Thus clothed with complete authority, the Managing Committee of professors has discharged its duties skillfully and conscientiously year after year, without friction with either the Trustees on the one hand or the Cooperating Institutions on the other; and such a thing as a deficit, which is the chronic ailment of institutions conducted upon the usual plan, is unknown and virtually impossible. Students of academic administration are invited to study the record of the Athenian School, which has passed beyond the period of experiment. A wise distribution of function has resulted, on the one hand, in keeping the School a part of the educational system of the institutions which support it, and, on the other hand, in concentrating in the hands of educational experts the full responsibility for the educational administration; there has been efficiency combined with democracy; and the clashing of authority, so commonly witnessed where the position of the faculty is ill defined or too narrowly limited to teaching and discipline, has been conspicuously absent. It is a record of which the Managing Committee, and doubtless the Trustees also, are justly proud.

During the war some of the cooperating colleges found it impossible to continue their support. The revenue from this source had fallen from $4,695.42 in 1917–1918 to $3,662.07 in 1918–1919, a loss of about twenty-two per cent, a severe loss, since at this time the income from the colleges, even at this reduced figure, was one-third of the total School income (income from securities in 1918–1919, $7,816.08). Capps noted that there were twenty-five institutions cooperating in the School’s support and that the number had not been increased in twenty years. This static list he vigorously described as an anachronism. He suggested the addition of Bowdoin, Hamilton, Goucher, Oberlin, Northwestern, Vanderbilt, Tulane and the State Universities of Virginia, Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin and Colorado. During his chairmanship all these were added except Vanderbilt (which joined in 1940), Tulane and Colorado. And in lieu of these he succeeded in adding the Bureau of University Travel, the Catholic University of America, the College of the City of New York, the University of Cincinnati, Crozer Theological Seminary, Drake University (for one year), Duke, George Washington University, Haverford, Hunter, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Rochester, Radcliffe, Swarthmore, Syracuse, Trinity, Washington University, Whitman College, the State Universities of Ohio and Texas, and the University of Toronto. The income from this source rose immediately. In 1921–1922 it was $8,733.29; for 1929–1930 it was ten thousand dollars.

To secure more publicity for the School Capps advocated that each cooperating institution mention in its catalogue the facilities of the School, which were open gratis to its graduates.

He further planned to secure extensive publicity for the School by articles of a popular nature in Art and Archaeology. Mitchell Carroll, who was then Editor-in-chief and represented the George Washington University on the Managing Committee, promised space, an offer which was later renewed by his successor, Arthur Stanley Riggs.

On the matter of deferred publication Capps spoke in no uncertain tone:

Referring to the problem of the School’s publications in general, the Chairman shares with the other members of the Committee the feeling that, while we have every reason to be proud of the work of research accomplished by our representatives in Athens, the time has come when the publication of discoveries which we have announced to be of the first importance must be pushed to early completion. Certainly the time has now come when no other task or preoccupation should be allowed to interfere with the prompt appearance, one after the other, of the books on the Erechtheum, the Propylaea, and Corinth. Corinth should, in fact, come first. It is therefore urgently recommended that every effort be made, by all the officers and committees concerned, to bring the three volumes mentioned to immediate completion. And the work already done at Corinth should be adequately reported in the preliminary publication before further excavations are undertaken, or funds solicited for them.

The cost of the final completion of work at Corinth and its publication was spoken of as a matter of fifty thousand dollars, a considerable underestimate, as the fact proved. Capps set himself to raise this fund as well as a permanent fund for excavation and research.

It has been noted that the final arrangements for the purchase of a lot for the women’s hostel had been announced by Capps while he was still in Athens. He now arranged for the building of the hostel itself by securing the appointment of W. Stuart Thompson as architect. His preliminary plans were formed, and a committee was appointed to secure the $150,000 necessary for the erection of the building.

The Auxiliary Fund, which he had founded, now had reached a principal sum of about ten thousand dollars, and interest from it could be used for current expenses. But this assistance was wholly inadequate to carry the increased expenses of the School.

Capps pointed out that the budget of $20,050 adopted for 1920–1921 was something like six thousand dollars in excess of the current income of the School. Though part of this was for nonrecurrent items and though part of it could be met from reserves accumulated, still it took a considerable amount of confidence in the future to pass and advocate this budget. Capps did not hesitate. He went a good deal further ; he closed his report with the bold statement that an additional endowment of at least two hundred thousand dollars was necessary and that at least half of this must be procured during the coming year.

The aim of Capps’s chairmanship was, then, (1) to increase the number of cooperating institutions; (2) to make the work of the School better and more widely known; (3) to publish the books on the Erechtheum, Corinth and the Propylaea; (4) to systematize and vigorously prosecute the further excavation of Corinth but preferably not till after these three publications had appeared; (5) to secure an endowment for excavation and research; (6) to erect a hostel for women; and (7) to more than double the endowment, and that without too much delay. This was no trifling program. No voice like this had been heard in the Managing Committee since the trenchant report of White in 1894 (Bulletin IV).

When Capps laid down the chairmanship twenty years later (1939), of these seven objectives all had been magnificently attained except the publication of the Propylaea.

In June, 1920, Capps was appointed, by President Woodrow Wilson, Minister of the United States to Greece and Montenegro. He promptly offered to resign his chairmanship, but the Executive Committee refused to entertain this suggestion and as before appointed Perry Acting Chairman. Capps sailed for Greece in August. While he was Minister in Athens he scrupulously refrained from active participation in the affairs of the School, though he could not withdraw his interest from what was the most absorbing activity of his rich and varied life.

There may be a difference of opinion regarding the effect on the nation of the defeat of the Democratic Party in the election of 1920. There can be no question that it was a blessing to the School, for it terminated Capps’s ministerial mission in March and sent him back to the United States in June, 1921, to devote himself again to the chairmanship. Perry presided at the meeting of the Managing Committee in May, 1921. The report for the year was written by Capps.

For the first time since 1914–1915 there was a student body at the School. (There had been one Fellow, part-time, in 1915–1916.) There were nine regular students, all Fellows. There were three Fellows of the Institute (two appointed before the war), one Fellow of the School and a Fellow in Architecture, two Charles Eliot Norton Fellows from Harvard, a Procter Fellow from Princeton and a Locke Fellow in Greek from Hamilton. Miss Priscilla Capps and Edward Capps, Jr., were associate members.

The stipend of the Fellows of the School and of the Institute was this year for the first time advanced to one thousand dollars. Among these Fellows at the School were several who were to maintain a long connection with it. Leicester B. Holland, Fellow in Architecture, was reappointed for the following year with the title Architect of the School and again for 1922–1923 as Associate Professor of Architecture. James P. Harland had been at the School the second semester of 1913–1914. He was now a Fellow of the Institute. He returned to the School twice later—1926–1927 and the second semester of 1939. Benjamin D. Meritt, Locke Fellow of Hamilton College, was the following year Fellow of the Institute, Assistant Director of the School (1926–1928), Annual Professor (1932–1933), Visiting Professor (1935–1936, first semester), member of the Managing Committee from 1926 on and Chairman of the Publications Committee 1939–.

Miss Alice L. Walker (Mrs. Georgios Kosmopoulos), who had been a student in the School 1909–1914, returned to Greece this year to work on the prehistoric remains about Corinth and the prehistoric pottery found there. This investigation was destined to be long continued. In 1939 she took the manuscript of her first volume to Munich, where she arranged to have it published by Bruckmann. When the book was printed, in 1940, it could not be delivered and probably is still in Munich. Volumes II and III are still “in preparation.”

Under the chairmanship of Professor Samuel E. Bassett the Committee on Fellowships recommended a change in the character of the examinations, which was approved by the Managing Committee. Under the new ruling the candidate was required to take examinations of a general character in Modern Greek, Greek Archaeology, Architecture, Sculpture, Vases, Epigraphy, Pausanias and the Topography of Athens and a more searching examination in one of the fields to be chosen by the candidate himself. The requirement had previously been Modern Greek and any three other topics.

The first open meeting in years was held at the School in March. Hill spoke on the excavations at Corinth, and Blegen on Korakou.

The progress of the School was signalized this year by the first automobile trouble. A Fiat camion and a Ford car had been obtained as a legacy, or spoils of war, from the Red Cross. Hill reported that the School trips had been unusually numerous and extensive, “owing to the speed of the camion.” These trips were diversified by all sorts of accidents to tires and running gear, causing delay and expense. The final debacle came when an elaborate interchange of locomotive activity with the students of the Roman School was attempted in the spring of 1920. The Athenian School were to proceed by train to Olympia and Messenia, thence by mule to Sparta. There they were to meet the Romans, who were to have gone by camion through Argolis. Here an exchange of transport was to be made, each school returning to Athens by the route the other had taken from Athens. The strategy was excellent, but the tactics faulty. The camion refused to leave Athens till repairs to vital organs had been effected. Meanwhile, the Romans proceeded to Nauplia by train, where the camion overtook them. At Sparta the exchange was made, but when the camion had transported the Athenians as far as Monemvasia it gave up the ghost. A disgusted chairman reported, “At last accounts the camion has been out of commission since April, 1920, on account of injuries undergone in the Peloponnesus trip.”

The Fortieth Annual Report (1920–1921) had contained this statement:

In accordance with the desire of the Committee, in which Dr. Hill fully shares, that no considerable new excavation, or even a continuation of the excavation of Old Corinth, should be undertaken until the officers of the School should have had time to catch up with arrears in the matter of publication, no programme for future excavations by the School itself has been proposed or considered. It is the Committee’s hope and expectation that for the next few years the Director and Assistant Director will devote the time which, in other conditions, they would be giving each year to the exploration of sites, in the search for new material, to the preparation for publication of the accumulations of earlier years.

Circumstances seemed to make a relaxation of this “substance of doctrine” advisable.

In October, 1920, Blegen, accompanied by Hill and the students of the School, stopped about halfway between Corinth and Mycenae for a casual investigation of a mound, Zygouries, which had seemed to Blegen to offer attractive possibilities. Here a very cursory examination revealed many traces of prehistoric culture, a bit of wall and many sherds. Lester M. Prindle, Charles Eliot Norton Fellow, found a marble idol that belonged to a type hitherto unknown on the mainland. Seager generously offered five hundred dollars for a trial excavation. [Fortieth Report, p. 17, states five hundred pounds, but the whole excavation cost less than one thousand dollars (Forty-first Report, p. 20).] Hill donated one hundred dollars given him by Mrs. Edward Robinson “for excavation.” At a further inspection the next March, Dr. Robinson offered to add five hundred dollars more to complete the excavation. Work was begun in April. Wace, of the British School, offered his assistance, and Holland, Harland and J. Donald Young, Procter Fellow of Princeton, joined the force.

This excavation was continued the next year (1922). A significant contribution toward defraying the expense was made by Mr. Carl B. Spitzer, of Toledo.

This excavation, made at the relatively small cost of about one thousand dollars, was one of the most successful undertaken by the School. It was shown that there had been a settlement here from 2400 to 1200 B.C. The earlier settlement was the more important. The plans of small houses separated by narrow, crooked streets were disclosed. Much pottery from this stratum was recovered. The Middle Helladic settlement (2000–1600 B.C.) was the least important. A “potter’s shop” belonging to the latest Helladic period was discovered in which about a thousand vases were found. In addition to this, Blegen during the second campaign was able to locate the burial place of this village. Here an Early Helladic cemetery was found. With the exception of a single grave discovered at Corinth these were the earliest examples of Early Helladic burial on the mainland. The objects found in these tombs were exceedingly valuable as establishing a connection with the Cyclades. There were also found graves of the Middle and Late Helladic periods.

When the objects found here were removed to Corinth, it was necessary to rent a special building to house them. Blegen at once made a preliminary publication of these excavations in Art and Archaeology. The final publication, a handsome volume with twenty illustrations in color, was issued by the School in 1928. (Plate XII)

An interesting arrangement was made this year with the Fogg Museum of Art, of Harvard University, for joint excavations. The Museum agreed to furnish not less than ten thousand dollars a year for five years. The School agreed to secure the necessary concessions and to attend to the formalities incident to the conduct of an excavation. Each party was to furnish one representative or more to oversee the work. The publication was to be sponsored by both institutions, the expense to be met by the Museum. This arrangement was obviously advantageous to the School, and it was hoped that such supervision as would be necessary could be furnished without interfering with the program of publication on which the Committee was determined.

This was the first of several joint excavations in Greece under the auspices of the School. D. M. Robinson’s dig at Olynthus and Lehman’s at Samothrace were later examples of such an arrangement. Miss Hetty Goldman was chosen by the Fogg Museum as their representative. She had been a student in the School for three years (1910–1913). She had excavated successfully at Halae. During the summer of 1921 Miss Goldman and Hill traveled extensively in Greece, the Islands and Asia Minor, investigating the possibility of digging at various sites. Colophon, about twenty-five miles south of Smyrna, was finally selected. Application was made to the Government at Smyrna in February, 1922. Hill spent ten days in March completing arrangements, and early in April the expedition set out.

Dr. Goldman was in charge with Miss Lulu Eldridge. The School was represented by Blegen and Holland, of the staff, and three students, Meritt, Franklin P. Johnson, Fellow of the School, and Kenneth Scott.

Most of the work was done on the acropolis. This rises terrace above terrace, as at Pergamon. On the main terrace the ground plans of several large houses were uncovered. Stairways and drains were cleared. These Greek houses proved to be of an early date, the earliest yet found except at Priene. A bathing establishment was also found, and the sanctuary of the Great Mother was located. A brief account of this excavation, written by Fowler, was published in Art and Archaeology, and a more complete statement appeared in Hesperia in 1944. Work was discontinued when the territory about Smyrna reverted from Greek to Turkish authority but was resumed for a brief time in the fall of 1925. The site proved unrewarding, and nothing further was done. Two publications were made, however, a preliminary article on the inscriptions by Meritt in the American Journal of Philology (1935) and an exhaustive discussion of the Colophonian house in Hesperia.

At the meeting in 1921 much dissatisfaction with the delay of the Erechtheum publication was manifest. On motion of Dr. Edward Robinson it was highly resolved that “the publication of the results of the investigation of the Erechtheum by the American School be not further delayed, and that no results of investigation later than the spring of 1921 be included.” Capps had personally seen each of the contributors. He was able to report that Dr. Paton would finish his chapter in 1922. Stevens’ work was complete, Fowler was making his final revisions, and Caskey was well along with the building inscriptions on which he had worked in Athens in 1921. It was hoped the printer would receive the material in 1922.

No such hope was expressed regarding Hill’s Bulletin on Corinth. It seemed likely that Paton, when released from the Erechtheum, might have to be assigned to this task, too.

The Propylaea book, though “in a somewhat more advanced state than a year ago,” was still further from completion than its author could wish.

This year the Auxiliary Fund, under the chairmanship of T. Leslie Shear, reached its high-water mark. The amount received was $10,751.32. Shear himself made a generous gift of five thousand dollars. It was hoped at the time that something like this amount might be realized annually. That has not been possible. For a considerable number of years the gifts amounted to about five thousand dollars annually but during the last few years of Capps’s administration they fell to about three thousand dollars. The very success which he attained in securing large gifts discouraged those who were able to give but a modest amount, and these constituted most of the personnel who made up the Auxiliary Fund Association.

One project begun some time earlier was completed this year. A piano had long been needed for the social rooms of the School. Mrs. A. C. McGiffert, of New York, had taken the matter in hand and with the assistance of Mrs. C. B. Gulick, of Cambridge, and others she raised funds to purchase a Mason and Hamlin Grand Piano, which is still appreciated by the students of the School.

Two other funds were begun in 1920–1921. One fund was in memory of Major Cyril G. Hopkins, of the University of Illinois, a member of the Red Cross Commission. He came to Greece at the request of Mr. Venizelos to advise the Greek Government as a soil expert. The value of his pamphlet on “How Greece Can Produce More Food” has proved the wisdom of Venizelos’ suggestion. He died at Gibraltar of malaria contracted in Greece. His friends at the suggestion of Dewing established this fund. The initial amount was $624.

The other fund was established in memory of John Huybers, an American press correspondent who died at Phaleron in 1919. His sympathetic understanding of the Greek people led his Greek friends to desire that his name might have a permanent place in an institution devoted, as he was, to American-Hellenic unity. This fund was $545. In neither case was there expectation that the fund would be very largely increased. The former amounts (1944) to $703.12, and the latter to $714.53. They remain part of the permanent School endowment and will continue to serve the friendly purpose for which they were established.

But the really memorable event of 1920–1921 was the beginning of Capps’s first campaign for a large endowment.

Capps realized that the time for such a campaign was unpropitious (it always seems to be) but unlike other chairmen he went ahead anyway. His motto seems to have been, “Today, Providence permitting; tomorrow, whether or no.” On June 1, 1920, he applied to the Carnegie Corporation and the General Education Board, asking each for an endowment fund of one hundred thousand dollars on condition that the Trustees and Managing Committee of the School raise one hundred thousand dollars. If both granted the request the School’s endowment would be increased by three hundred thousand dollars; if only one did so, by two hundred thousand dollars, the minimum absolutely required by the needs of the School. A similar request was also made to the Rockefeller Foundation.

The General Education Board was inhibited by its charter from assisting educational institutions in foreign countries, and the Rockefeller Foundation had made other commitments, but the President of the Carnegie Corporation, J. R. Angell, brought the matter to the attention of his Board of Trustees in the fall after Capps had gone as Minister to Greece. Apparently no action was taken at that meeting. Before their spring meeting Dr. Edward Robinson, who had been in Greece during the winter and had thus had an opportunity to study the work of the School personally, wrote a letter describing the achievements of the School and its needs to Dr. Henry S. Pritchett, a member of the Board of Trustees of the Carnegie Corporation. Dr. Pritchett had earlier been deeply interested in the School, and probably this letter to him and his influence in the Board were determining factors in the favorable decision at which they then arrived.

After several conferences between Capps and Allen Curtis, Treasurer of the School Trustees, and President Angell, on July 18, 1921, the Carnegie Corporation made this conditional offer to the Trustees and the Managing Committee of the School. The Carnegie Corporation would grant the School’s request for one hundred thousand dollars for endowment if the School would raise for endowment $150,000 before January 1, 1925. Further, to meet the immediate needs of the School, the Carnegie Corporation offered to pay five thousand dollars a year for five years conditioned on the School’s raising seventy-five thousand dollars by July 1, 1923. This was the first but by no means the last of Capps’s triumphs as an administrative financier.

The immediate payment of the first five thousand dollars enabled the Managing Committee to revise its budget for 1921–1922. The budget for 1920–1921 had been $20,050. It had been reduced to $13,250 for 1921–1922. It was now possible to increase this to eighteen thousand dollars, including an item of one thousand dollars for the purchase of annuities in favor of the director and the assistant director. Blegen had been given the title of assistant director at the annual meeting in 1920 in recognition of his distinguished services to the School as secretary from 1913 to 1920. He was the first to hold this title.

An organization committee was appointed, consisting of Capps, chairman, Perry and Allen Curtis. A Committee on Endowment was created by them and fully organized by November 1, 1921. The Committee on Organization were made the officers of this larger committee. Work was prosecuted with all the energy and enthusiasm characteristic of Capps.

As a preliminary to the endowment campaign the committee felt that more publicity of a dignified character for the School was necessary. Mitchell Carroll, a member of the Managing Committee, generously gave a whole issue of Art and Archaeology, of which he was editor, to an account of the School. This appeared in October, 1922. Harold North Fowler devoted his entire summer to writing and editing the articles, which were profusely and beautifully illustrated. They included a brief history, of the School and its earlier excavations, by Fowler; a chapter on the excavation of Corinth, written by Hill and edited by Fowler; a chapter on prehistoric sites by Blegen. “The Researches on the Athenian Acropolis” was contributed largely by Dinsmoor. “The Publications of the School” was written by George H. Chase, who also contributed, with the assistance of Leicester B. Holland, the article on Colophon. An interesting contribution on the opportunities for study in the Byzantine field at the School was contributed by Dr. Robert P. Blake.

When the annual meeting of the Managing Committee was held the following May, seventy thousand dollars had been raised. By August 1, 1922, the total was $89,506.83, well over half the amount sought in less than a year.

And now a very welcome testimony to the importance of the School as an American institution of the highest standing came from Mr. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., in whose behalf Mr. Raymond B. Fosdick wrote in June, 1922, to Capps, stating that after careful investigation Mr. Rockefeller had decided to give the School, preferably for permanent endowment, one hundred thousand dollars, provided the School was successful in its effort to raise the $150,000. Meanwhile, he very generously offered to pay the Trustees of the School the interest on his gift at five per cent. His offer was limited to two years, thereby setting forward the limit for completing the campaign for the $150,000 from January 1, 1925, to June 19, 1924.

More than a year before that date arrived, Capps was able to announce the completion of the task. On May 20, 1923, there had been subscribed $147,000. Dr. Joseph Clark Hop-pin had pledged two thousand dollars if the fund was completed before July 1, and Dr. Edward Robinson had asked to be allowed to give the last thousand dollars. He had already given the first thousand. Before July 1 additional gifts raised the total to $160,000. The final total was $165,473.99.

All of this amount, as well as the hundred thousand dollars from the Carnegie Corporation and the hundred thousand dollars from Mr. Rockefeller, was for permanent endowment. Of the remainder, $83,555 was given for unspecified purposes. Other endowment funds which were created at the time and which helped to make up the grand total were the American Red Cross Commissions Fund, the Hopkins and Huybers Funds, and funds to capitalize the participation of Adelbert College of Western Reserve University, Harvard University, the University of California and New York University.

Three funds were also started in honor of the first three chairmen of the Managing Committee, John Williams White, Thomas Day Seymour and James Rignall Wheeler. At the time it was hoped that these might be built up to twenty thousand dollars each and that then each would support a fellow in residence at Athens with a stipend of one thousand dollars. The fellowship in Seymour’s memory was to be awarded for the study of the Greek Language, Literature and History. These fellowship funds have later been raised to thirty thousand dollars each, and a fourth in honor of Edward Capps was added by the Trustees after his retirement from the chairmanship. Seymour, White, Wheeler and Capps Fellows were all appointed in 1940. The details of these gifts with a complete list of all the donors are given in Capps’s meticulous report for the year 1922–1923.

When Capps was made chairman in 1918 the endowment accumulated in thirty-six years was less than $150,000. His active work as chairman had begun in 1920. In less than four years he had increased the endowment to more than five hundred thousand dollars.

During the year 1921–1922 there were four regular students at the School. Meritt was spending his second year in Athens, as Institute Fellow. He devoted this year largely to work on Thucydides, spending much time in Elis, Acarnania, Aetolia and the Chalcidic Peninsula. He prepared a paper on the Apodotia campaign of the Athenian general Demosthenes and by careful study of the tribute lists was able to point out unfairness in Thucydides’ treatment of Cleon.

Miss Alice Walker continued her study of Corinthian pottery but spent considerable time in investigating prehistoric sites in the Peloponnesus, especially in Arcadia.

This was the year in which Blegen was completing his dig at Zygouries, and, in fact, the attention of the School was being drawn more continuously to the prehistoric sites. Blegen suggested a complete survey of the Peloponnesus with this in view. Another promising site near Thisbe in Boeotia was also considered. The Managing Committee was so impressed with the work of Blegen that they voted an appropriation of fifty dollars at the meeting in May, 1922, for a small investigation on Mount Hymettus, where the year before Prindle had found a few geometric sherds in a hollow near the summit. A preliminary excavation the next year disclosed a deposit of considerable depth containing many sherds of the geometric period and some of the classical age. A few of the geometric fragments were scratched with rude lettering. In 1924 this excavation was completed. A very large number of shattered vases was found, mostly heaped together, apparently votive offerings from a shrine. Some two or three hundred were nearly intact. These were removed to the National Museum for repair and study. The expense of this excavation was met by T. Leslie Shear.

In March and June, 1939, Rodney Young, of the Agora staff, made a supplementary excavation here. Foundations were discovered indicating a sanctuary, and a three-letter inscription that suggested Heracles as the deity worshipped. An altar was found with another sanctuary nearby, identified as the sanctuary of Zeus, and a stele which, it was suggested, formed the basis of the statue of Zeus of Hymettus, mentioned by Pausanias. The altar would then probably be the altar of Zeus of the Showers, also said by Pausanias to be on Mount Hymettus. Many of the pieces of pottery found were inscribed, but none seems to be earlier than the seventh century B.C.

The Managing Committee took steps at its meeting in 1922 to secure closer relations with the staff of the School and better to acquaint the members of the Committee with what was going on in Athens.

These regulations provided that the director should each year before May 1 provide the chairman of the Managing Committee with a list and description of the courses to be offered during the year, a list of the proposed School trips and of the excavations to be made. The annual professor was to outline his work for the coming year during the preceding December. Monthly reports were to be made by the director and the associate director. The annual professor and other members of the staff were to submit, through the director, reports on January 1 and at the close of the year. The director was further asked to file with the chairman before May 1 each year a detailed report of the year’s work “which shall indicate clearly all changes from the proposed plan of work, with the reasons therefor.” The Executive Committee was empowered to approve the plan of the year’s work or to suggest changes. Explicitly no excavation was to be undertaken by any member of the School staff “unless provided for in the Budget, or approved in advance by the Executive Committee.” The idea of publishing the courses in advance recalls White’s suggestion, but the general tone of these resolutions, unanimously recommended by the Executive Committee, suggests growing tension between the Managing Committee and the staff. For a time, however, they seem to have served a very useful purpose.

Dinsmoor’s book on the Propylaea was now pronounced to be as nearly complete as it could be made till the author could revisit Athens to verify details. Hill’s Bulletin on Corinth showed no progress, but the article on the excavations which he was preparing for Art and Archaeology was felt to be progressing in the right direction. The hopes for the publication of the Erechtheum had not been fully realized, but such progress had been made that it seemed probable that part of the material would reach the printer in the spring of 1923.

Capps concludes his report for this annus mirabilis (1921–1922), which assured the conditional gifts of one hundred thousand dollars each from the Carnegie Corporation and Mr. Rockefeller, with this paragraph:

I have reserved for the last place in this Report the most remarkable piece of good fortune that has fallen to the lot of the School since its foundation—the gift it has received of the Gennadius Library, of the building to house it, and of the land in Athens on which to build it.

The remarkable story can best be told in Capps’s own words:

The magnificent Library of His Excellency Dr. Joannes Gennadius, who for many years and during the late war represented the Greek Government at the Court of St. James, has long been known to connoisseurs as, within its field, without a rival in the world. Housed in London in the residence of Dr. Gennadius, it has drawn visitors from every country, and was known to contain collections of unsurpassed completeness for the illustration of Hellenic civilization in every age and numberless individual treasures of unique beauty and rarity. . . . . The items number between 45,000 and 50,000.

When President Harding proposed the Washington Disarmament Conference, Dr. Gennadius was living, as the Dean emeritus of the Greek Diplomatic Service, in well-earned scholarly leisure among his books in London. His government summoned him from his retirement to attend the Conference as the representative of Greece, paying to the United States the compliment of sending here one who had rendered to his country and to the Allies distinguished service during the war, who enjoyed the friendship and esteem of the statesmen of the other countries to be represented in the Conference, and who, besides, was widely known among scholars and collectors the world over. After the work of the Conference was finished, he and Madame Gennadius stayed on in Washington for a time. It was during this period and in the following circumstances that the possibility of the School’s receiving from Dr. Gennadius the gift of his Library came to be considered.

It had long been the wish of Dr. Gennadius that his Library and Collections should ultimately go to Athens, there to be used by the scholars of all nations; but owing to their great value, the physical requirements of their proper care, and the scholarly requirements of their use, he had as yet found no means of carrying out his purpose, and the troubled condition of Europe and especially of Greece seemed to make his dream of a great establishment in Athens, worthy of the Library and adequate to its scholarly employment, difficult if not impossible of immediate realization. He spoke of this problem to Professor Mitchell Carroll, Secretary and Director of the Archaeological Society of Washington, and Professor Carroll suggested the possibility that the American School at Athens might be able to provide the building and the custody of the Library. I was accordingly invited, in March 1922, to a series of conferences with Dr. Gennadius and Professor Carroll, in which this possibility was fully discussed from every point of view. Professor Carroll, a pupil of the School and a member of the Managing Committee, had not only prepared the way for these conferences, but contributed many practical suggestions toward the solution which was finally agreed upon. Dr. Gennadius showed himself most sympathetic toward the School, then in the midst of an arduous endowment campaign and possessing no general resources which could be used for a building or even the adequate custody of the Library, and readily adapted the conditions of his gift to what seemed at the time to be within the reasonable expectations of the School. The letter offering the Library to the School was addressed to Professor Carroll and myself, under date of March 29, 1922. I quote here the first part of the letter, omitting the description of the Library which follows:

“In accordance with the preliminary conversations which I have already had with you, I now beg to place before you, in a more detailed and precise form, the proposal I made, with the full approval and concurrence of my wife, Madame Gennadius, for the presentation of my Library and the collections supplementary to it, as hereinafter summarily described, to the American School at Athens, on the following conditions:

“(1) That the said Library and Collections be kept permanently and entirely separate and distinct from all other books or collections, in a special building, or part of a suitable building, to be provided for this purpose.

“(2) That the Library, etc., be known as the Gennadeion in remembrance of my Father, George Gennadius, whose memory is held by my countrymen in great veneration and gratitude.

“(3) That as soon as practicable a subject catalogue of the whole Library and of the collections be completed and published on the same principle of classification as the Sections already catalogued by me.

“(4) That no book or pamphlet, or any items of the Collections, be lent, or allowed to leave the Library; but that rules be drawn up for the proper and safe use of the books, etc The rarest and most valuable items may even be withheld from any hurtful use, at the discretion of the Directorate.

“(5) That a competent and specially trained bibliognost be employed as Librarian and Custodian.

“(6) That the special section, containing the published works of my Father, of other members of my family, and my own publications, be kept apart, in a separate bookcase, as now arranged in the Library. Likewise the publications of my wife’s Father and of his family.

“(7) That the Professors of the University of Athens, the Council of the Greek Archaeological Society, and the members of the British, French, and German Schools at Athens be admitted to the benefits of the use of the Library and of Collections on special terms and conditions to be determined by the Directorate.

“(8) That if ever the American School of Archaeology in Athens ceases to exist, or is withdrawn from Greece, the Library with all the supplementary collections, without exception, shall then revert to the University of Athens on the same conditions as above in respect to their preservation and management.

“My wife and I make this presentation in token of our admiration and respect for your great country—the first country from which a voice of sympathy and encouragement reached our fathers when they rose in their then apparently hopeless struggle for independence; and we do so in the confident hope that the American School in Athens may thus become a world center for the study of Greek history, literature and art, both ancient, Byzantine and modern, and for the better understanding of the history and constitution of the Greek Church, that Mother Church of Christianity, in which the Greek Fathers, imbued with the philosophy of Plato, first determined and expounded the dogmas of our common faith.

“Holding as I do a strong preference for giving away during life what one can, rather than willing after death what one may no longer use, I am ready to make over to the School the whole of the said Library and the other collections as soon as provision for their due housing has been made; and I pray that my wife and I may be spared to enjoy the sight of their actual utilization in full working order.”

During the period of negotiations culminating in this most generous offer, I had been unable to consult with the President of the Board of Trustees owing to his serious illness; but as soon as he was able to attend to affairs Judge Loring wrote the following letter of acceptance to Dr. Gennadius, under the date of April 12:

“2 Gloucester St.

Boston, Mass.

April 12, 1922.“His Excellency Mr. J. Gennadius

Envoy Extraordinary of the Royal Government of Greece,

Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D. C.“My dear Mr. Gennadius:

“The Chairman of the Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Professor Capps, has transmitted to me, as President of the Board of Trustees of that institution, your most generous offer, dated March 29, 1922, of your magnificent private Library and supplementary Collections as a gift to the School, as a memorial to your distinguished father, Mr. George Gennadius, together with the conditions attaching to your offer.“I regret that illness has prevented my earlier acknowledgment of your proposal, whose extraordinary character, as well as the high motives which have inspired your action, have not failed to impress me deeply. No more fitting memorial to George Gennadius could have been conceived by his equally distinguished son; Greece is obviously the most appropriate home for your remarkable collection of documents relating to the history of Hellas and the Levant: and Greece as well as America are equally benefited by the permanent establishment in Athens, under the care of the American School, of your Library and Collections, the result of many years of scholarly selection. May I express to Madame Gennadius and to you my profound appreciation of the honor and recognition that your proposal itself confers upon the American School at Athens.

“I accept, in the name of the American School and its Trustees, your generous gift and the conditions subject to which you make it—with the proviso, however, which necessarily attaches to the acceptance of so heavy a responsibility before we have had time to ascertain whether or not we can obtain the funds with which to fulfill the obligations we should be assuming—viz., that before taking title to the Library and Collections we must first consult with possible donors of the necessary funds for the erection of the building or wing to house the Library. Mr. Capps tells me that he has already laid the matter before one benevolent corporation, and I can assure you that he will proceed with all diligence in his search. I trust that, even in these difficult times, we may soon meet with success.

“If the undertaking is consummated in accordance with your highminded and generous proposal, I feel confident that the Gennadeion of the American School in Athens will become the resort of all scholars of the world who devote themselves to the interpretation of the Hellenic civilization in all its branches, from the Ancient Greece, through the Byzantine Empire, to the Greece of today. And I am sure that I share with you the belief that your gift to the world of scholarship, through the agency of the American School, will greatly strengthen the ties, already close, that bind the Republic of the West to your native country, the fountain-head of our European civilization.

“Accept, Excellency, for Madame Gennadius and yourself the assurance of my sincere and profound gratitude, in the name of my colleagues of the Board of Trustees.

“Very sincerely yours,

(Signed) “William Caleb Loring,

“President of the Board of Trustees.”Dr. Gennadius was momentarily expecting to be ordered home by his government and the margin of time for finding the money for the building to house the Library was slight, if the transaction was to be completed before his departure. There was also the question of the site for the building, for which we should have to depend upon the generosity of the Greek Government. Furthermore, it was difficult, without detailed knowledge of the space required for the books and collections of the Gennadius Library, to estimate the size and probable cost of the building. But fortunately Dr. Gennadius, on the one hand, possessed the most exact recollection of the number of volumes, their size and grouping, and the space required for the exhibition of the rarest items; and Mr. W. Stuart Thompson, on the other hand—a practicing architect of New York who had once held the Carnegie Fellowship in Architecture at the School and had superintended the construction of the Library Addition to the School building—had an exact survey of the tract of land lying to the north of the present School property just south of the aqueduct of Hadrian on the slopes of Mt. Lycabettus, which was the only appropriate and available plot near the School for such a building. Tentative plans and estimates were therefore made by Mr. Thompson on the assumption that the proposed site could be obtained, and on April 8 I laid the whole situation before Dr. Henry S. Pritchett, Acting President of the Carnegie Corporation.

In the negotiations which followed I had the invaluable cooperation of Dr. Edward Robinson of the Managing Committee, who had personal knowledge of the Gennadius Library in London and instantly saw how advantageous for the School its acquisition would be. “An acquisition like this,” he wrote to Dr. Pritchett, “would at once place the School in the front rank of learned bodies in Europe, and enable it to afford unparalleled facilities to scholars from all parts of the world who visit Athens. Such an opportunity does not come once in the lifetime of every institution, and if allowed to pass by it can never recur.”

On May 20 the Carnegie Corporation voted a grant of $200,000 for the erection of the Gennadeion. The conditions attached to the grant were “that a building plan satisfactory to the Corporation be submitted, that the building be begun not later than January 1, 1924, and that the building be built and completed, ready for use, free of debt, including all architect’s fees and other charges, within the limits of the appropriation.”

Meanwhile an application was made to the Greek Government, through Director Hill, for the expropriation of the desired site, which was the property of the Petraki Monastery. In this transaction a letter which Mr. Elihu Root, as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Carnegie Corporation, wrote to the Prime Minister of Greece played so important a part that it should be quoted here as a matter of record; it is valuable also as showing the considerations which moved the Corporation to make its prompt and generous grant:

“Carnegie Corporation, 522 Fifth Avenue,

New York, June 6, 1922.“His Excellency

“The President of the Ministerial Council of the Kingdom of Greece“Sir:

“I have the honor, on behalf of the Trustees of the Carnegie Corporation, formally to make known to Your Excellency and your associates of the Ministerial Council, that the Carnegie Corporation has voted an appropriation of $200,000 to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens for the erection of a building to accommodate the Library and Collections which His Excellency, Mr. Joannes Gennadius, citizen of Greece and Dean of the Greek Diplomatic Service, has recently presented to the School.“The Corporation was moved to make this contribution, not only by its deep interest in the American School, which we are happy to think worthily represents American scholarship in the capital of Greece, but also by the desire to make prompt and adequate recognition, on the part of America, of the remarkably generous, public-spirited and enlightened act of Mr. Gennadius. We cordially sympathize with his twofold purpose—both to enrich the scholarly resources of his native country for the use and benefit of the scholars of all nations who resort to Athens for the study of the Hellenic civilization, and at the same time to promote and confirm the long-time friendship between the peoples of Greece and the United States of America by means of a visible monument in Athens and a continuing beneficent stream of influence flowing from his foundation. We trust and believe that his purpose will be realized.

“I take this occasion to express to Your Excellency our appreciation of the fine spirit of cooperation which the Greek Government, on its part, has manifested in undertaking to assist the American School to procure, as a site for the Gennadius Library, the tract of land adjacent to the present property of the School. It was with full knowledge of your generous action, and in the confident belief that it would speedily be crowned with success, that our Trustees have made the grant for the erection of the building.

“Accept, Excellency, the assurance of my distinguished consideration.

“Sincerely yours,

(Signed) “Elihu Root,

“Chairman of The Board of Trustees.”Mr. Root’s letter, in a modern Greek translation, was read in Parliament and was received with enthusiasm. A bill was soon introduced by the Government, and in spite of the pressure of business of the most distressing nature (this was only a short time before the Smyrna disaster) pushed through to its passage. By this bill the tract of land which we desired was expropriated, with the consent of the Petraki Monastery, to the perpetual use of the School for the Gennadeion. The Municipal Council of Athens afterwards vacated the two streets which had been projected, but never built, running through this plot, and added the vacant ground east of this plot to the forest preserve which covers the upper slopes of Mt. Lycabettus. The School property is therefore protected on the north and east sides from building encroachment. The negotiations connected with the acquisition of this land were, in the nature of the case, complicated in the extreme, and beginning in May were not finished for many months. The School is under the greatest obligations to Director Hill for his inexhaustible patience and resourcefulness in the conduct of this business, which he followed through changes of government, political and social disturbances, and legal complications until the land was wholly ours to build the Gennadeion upon. Probably no other person, Greek or foreigner, could have succeeded in the circumstances, in spite of the utmost good will on the part of all the Greek authorities concerned.

The following were appointed as members of the Building Committee by the joint action of the Managing Committee and the Board of Trustees: Dr. Edward Robinson, Professor Perry, Mr. Allen Curtis, Treasurer, Professor W. B. Dinsmoor, Secretary, and Professor Capps, Chairman. Mr. W. Stuart Thompson was sent to London to take exact measurements of the Gennadius Library, and on his return Messrs. Van Pelt and Thompson submitted a series of studies of the projected building. These having been laid before the Carnegie Corporation and approved as the basis of the design, the Building Committee recommended to the Trustees the appointment of Messrs. Van Pelt and Thompson to be the architects of the building. This was done in July, and a formal contract with this firm was executed by the Trustees. During the summer the design and plans were perfected, so that in the early autumn estimates might be made as to the probable cost of the building, with the expectation of letting the contracts during the winter and begin the actual work of construction in the spring of 1923. Mr. Thompson will go to Athens to superintend the construction, and it is our hope that the building may be completed and ready for use by the autumn of 1924. A full description of the site and the building is reserved for the next Annual Report.

It is impossible here to make suitable acknowledgment to all who have contributed in some essential way to making possible this notable enlargement of the scholarly resources of the School, but I can at least mention their names again. To Professor Mitchell Carroll is due the original suggestion which bore fruit in the magnificent gift of Dr. Gennadius; Mr. W. Stuart Thompson gave valuable aid when it was most needed, before Dr. Gennadius’ decision was made to give his Library to the School; Dr. Edward

Robinson, immediately appreciating the vast significance to the School of the acquisition of the Library, lent the weight of his influence to gaining for the project the favorable attention of the Carnegie Corporation; Dr. Henry S. Pritchett, representing the Corporation, in the negotiations, showed a scholar’s enthusiasm for the rare opportunity so unexpectedly offered to the School and must have presented our cause to his associates with conviction, so prompt and generous was their response; Mr. Root so skillfully communicated to the Greek Government the decision of the Corporation as to insure its favorable action on our application for the site; and Dr. Hill in Athens rendered invaluable services as diplomat, lawyer and director of legislation.The gratitude of the School and its governing bodies to Dr. Gennadius and Madame Gennadius is boundless. The recognition which came to them during the few weeks of their sojourn in America after the public announcement of their gift was a slight and inadequate expression of the sentiments which all sections of the American people feel. The Washington Society of the Archaeological Institute of America elected him to honorary membership ; George Washington University conferred upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters, and Princeton University that of Doctor of Law; and the Secretary of State took a special occasion to convey to him personally the thanks of the nation. The Managing Committee has spread upon its records the following letter, which Professor Perry as its Secretary addressed to Dr. Gennadius on May 20, 1922:

“Your Excellency:

“The Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, at its Annual Meeting held a few days ago, laid upon me the pleasant duty of expressing to you its lively sense of the signal honor done to the School, and through the School to the United States of America, by the munificent and unparalleled gift of your great library and the accompanying collections; and of conveying to you the profound gratitude of the Committee not only for the gift itself but also for the confidence you have thereby shown in the ability of the School to administer a trust of such magnitude and far-reaching importance. Your generosity makes possible not only the broadening, along the old lines, of the work of our institution as strictly a ‘School of Classical Studies,’ but also its development, in many new directions, as an institution of research in fields where hitherto we have been unable to tread.

“The members of the Committee understand fully how great and how honorable is their responsibility in undertaking to provide for the care and administration of the library and the proper utilization of its advantages; and we beg to assure Your Excellency that we and our successors will in every way endeavor to prove ourselves worthy of the distinction conferred upon us.”

The Gennadeion Library and the small houses connected with it by pillared colonnades make one of the most beautiful among the beautiful buildings of Athens. The two houses accommodate the librarian and the annual professor.

As erected, the actual group occupies a little more ground than had originally been planned. This was made possible by the generous action of the Greek Government in expropriating land for the site. The additional space made it possible to place the residences a little farther from the library, a change which greatly enhanced the beauty of the group, which now has a frontage of 187 feet and a depth of 117 feet. The Gennadeion itself is a rectangular building 79.5 by 55.5 feet. So pleased were the members of the Carnegie Corporation with the model submitted that they voted an additional fifty thousand dollars so that this entire structure—not the façade only—might be marble. (Plates XIII, XIV)

It would have been natural to construct the Gennadeion of Pentelic marble, but the quarries could not deliver the desired amount, nor was the quality of their output at all attractive. It was a white marble but shot through with bluish veins. The appearance would have resembled cipollino. Thompson, therefore, very wisely decided to use marble from the Island of Naxos. This Naxian marble is harder than Pentelic but does not have the large crystals so characteristic of the Naxian marble used for ancient statues and buildings. It retains its white color and does not take on with age the soft brown shades that add charm to the Parthenon and the Propylaea. The eight columns that adorn the façade are, however, Pentelic.

Building was begun promptly. The excavations were started on May 1, 1923, and on the twenty-seventh the monks of the Asomaton Monastery performed the ceremony of laying the foundation stone. On Christmas Day the lintel of the main doorway was lowered into place, and on it the workmen placed wild onions to avert the evil eye.

This onion poultice seems not to have been effective in relieving labor troubles, for by these Thompson was hampered during 1924. He dealt with the strikes in a masterful fashion. He declared an open shop and imported a new lot of stonemasons from Constantinople. The insufficient supply of water provided by the city system he remedied by sinking an artesian well, which incidentally proved a godsend to the occupants of the School during a water famine created in the second World War in 1944 when the city’s water mains were cut by Greek guerillas. Thompson com-batted the problem of rising prices by buying material in large quantities and storing it till wanted. But in spite of all he could do, the shortage of material, particularly marble, and the rising cost of labor and supplies made it clear that the buildings could not be completed for the $250,000 allocated by the Carnegie Corporation. Capps presented the situation to them, and they voted an additional twenty-five thousand dollars so that the original design might be carried out in full. The final amount received by the School for the Gennadeion Library was $275,000.

It was hoped that the Library might be ready for use in July, 1925, but it was not till fall that the Librarian, Dr. Gilbert Campbell Scoggin, was able to begin unpacking the books.

The dedication of the Gennadeion took place on April 23 and 24, 1926. Extensive preparations for the event had been made in America and in Athens. Capps reached Athens in March. Dr. and Mrs. Gennadius came on April 13. They were entertained as guests of Dr. and Mrs. Scoggin, and they actually lived again with the books, the collection of which had been a lifelong pleasure. Dr. and Mrs. Pritchett came from America. Seven members of the Board of Trustees were present, including the President, Judge Loring; the Vice-President, Frederick P. Fish; the Secretary, A. Winsor Weld; and the Treasurer, Allen Curtis. Mr. Van Pelt and Mr. W. Stuart Thompson, the architects who had designed and constructed the building, were there. To have completed the group of buildings in twenty-four months under the trying conditions that vexed Greece was an accomplishment of which they might well be very proud. Ten members of the Managing Committee, including Ralph V. D. Magoffin, President of the Archaeological Institute,

attended the ceremony. The entire list of delegates from America numbered 104.

Dean Walter Miller, the Annual Professor for 1925–1926, was delegated to conduct the guests from America on their visits to the museums and monuments of Athens and on short tours about Greece. He met the first group at Patras on April 6 and continued to interpret the country he so loves to his countrymen throughout the month. He led two excursions to Olympia and the Argolid, and two to Boeotia and Delphi, besides giving a dozen half-day programs in Athens on the Acropolis and in the museums.

The official guests included Madame Pangalos and Major Zervos, Captain Laskos and Captain Gennadis, aides to the President of the Republic, the Ministers of Foreign Affairs and of Education, the Mayor of Athens, with their wives, the British Minister and Lady Cheetham, the Austrian Consul General and Madame Walter, the American Consul General and Mrs. Garrels.

The Gennadeion was finally presented by Dr. Pritchett, representing the Carnegie Corporation, to Judge Loring, representing the Board of Trustees, and by him to Dr. Capps, as Chairman of the Managing Committee.

The packing and removal of the books from London to Athens presented a problem in itself. Dr. Gennadius very generously took it upon himself to superintend personally the dismantling of his London library and the oversight of the packing. The books were all put in perfect condition, especial care being given to those volumes encased in rare and precious bindings, nearly a thousand in number. In this work Dr. Gennadius had the assistance of experienced experts, notably Mr. Constantine Hutchins. The books were packed carefully in 192 zinc-lined cases. The cases were soldered shut and stored in London till they were shipped to Greece, in 1924. There they arrived safely.

The mere enumeration of the classes into which the boxes were divided for purposes of record gives some faint indication of the unique character of the splendid collection: Manuscripts, Classical Authors, Family Collections, Archaeology and Art, Editions de luxe, Geography and Travels, Natural History, War of Independence, Periodicals, Historians, Bibliography and Memoirs, Greek Language, Theology, Bibliography, Modern Greek Literature, Question d’Orient, Turkey and the Slav Countries, World War, Balkan Wars, Choral Music, Byzantine Literature, Poetical Works.

One of the obligations assumed by the School in accepting the gift of the library was the publication of the catalogue. As a preliminary to this Dr. Gennadius had prepared a great catalogue raisonné, contained in many typed quarto volumes. He had completed this work for about three-fourths of the volumes before they left London. Each volume is herein described in detail, with many interesting facts concerning its history and acquisition. In some cases, as the notes on the work and the correspondence of the Greek patriots, Adamantios Corais and George Gennadius, the father of the donor, this catalogue gives many facts which are of great value for the history of modern Greece. Dr. Gennadius also prepared for publication in Art and Archaeology an article on “Bookbindings: Their History, Their Character and Their Charm,” illustrated from some of the rare volumes in his own library. For working purposes a card catalogue was at once begun.

To care properly for this collection there was needed not so much a professional librarian alert to all the pitfalls of the Dewey decimal system as a bibliophile who would appreciate these rare volumes and cherish them with something of the loving care bestowed on them by Dr. Gennadius. In the words of the donor, a “bibliognost” was required.

For this post the Managing Committee selected Gilbert Campbell Scoggin, a graduate of Vanderbilt with a doctorate from Harvard. He had been a professor of Greek at the University of Missouri and Western Reserve University and had lectured at Harvard. But above all he was a “collector” of books in his own right.

To commemorate this princely gift the Trustees and the Managing Committee decided to issue a volume, Selected Bindings from the Gennadius Library. This, as Judge Loring said in a prefatory letter of dedication printed in this volume, was offered to Dr. Gennadius “as a slight expression of our gratitude.” It was a sumptuous volume, forty-two pages of letter press, thirty-nine plates, twenty-six of them in full color, giving a very adequate idea of the rich and varied bindings that glorify this library. Dr. James M. Paton had editorial charge of the volume. Dr. Lucy Allen Paton wrote the introduction and the description of the plates. An edition limited to three hundred copies was done by the Cheswick Press of Messrs. Whittingham and Griggs, of London.

The disaster to the Greek army in 1922, the burning of Smyrna and the tragic transportation to Greece of all the Greek residents of Turkey brought the School, through its director, into immediate contact with the Athenian population.

The condition of these refugees in Athens was pitiful in the extreme. An Athenian-American Relief Committee was formed, with Hill as Chairman. To this work he devoted himself

wholeheartedly, bringing to it his wide knowledge of Athenian resources and his persuasive personality. No American in Athens could have done more. This committee functioned till the Red Cross could take over.

In 1922–1923 there were four men and six women in residence. Pending the building of the hostel the women students had been forced to room in private dwellings. With the overcrowding of the city, due to the influx of refugees, this now became difficult or impossible. In this emergency the chairman and the director decided to allow some of the women to occupy rooms in what had been the men’s main dormitory at the east end of the School building. This solution was approved by the Managing Committee at its meeting in May, 1923, but there was considerable discussion, and a motion to allow the director a free hand in assigning rooms to students of either sex was displaced by a substitute motion transferring this discretionary power to the chairman and expressing an “earnest hope” that the emergency arrangements of the year 1922–1923 might not recur.

This discussion naturally revived in acute form the question of a women’s hostel. There being no immediate prospect of this being built, the suggestion was made in the Managing Committee that an annex might be rented which could be used for the accommodation of the women. Hill, resourceful as ever, at once produced a suitable dwelling, the palace of Prince George on Academy Street. This was rented by the School for 1923–1924. Since there were, however, only two women registered for that year, it was used to accommodate Mr. W. Stuart Thompson and his family and Professor and Mrs. Buck, of the School staff. The School continued to rent this property till Loring Hall became available to house amply both staff and students.

A pleasant incident of this year was a cruise among the Greek Islands (Aegina, Delos, Paros, Melos, Thera, Crete), on a yacht chartered by Mr. George D. Pratt, to which the members of the School were invited. Mr. Pratt further showed his interest in the work of the School by a gift the next year of five thousand dollars for the excavation of a site “preferably in Attica.”

As has been so often noted, the publication of the Erechtheum volume had been vexatiously delayed. This year, at last, tangible results were achieved, “principally,” as the Committee on Publications stated, due to the energy of Capps. The note of irritation engendered by hope long deferred is evident in such statements as, “Under his [Capps’s] urgings Mr. Hill has begun to send final notes to Professor Paton.” At last the Harvard Press was beginning to put this book into type. Capps made the cautious prediction, the result of so many disappointments and so many unfulfilled hopes, that “the process of proof reading will be slow” and that some conferences between the editor, Paton, Stevens in Rome and Hill in Athens would be necessary.