A Point within a Network: Joseph L. Rife Discusses On the Edge of a Roman Port

On the Edge of a Roman Port: Excavations at Koutsongila, Kenchreai, 2007–2014 (Hesperia Suppl. 52), edited by Elena Korka and Joseph L. Rife, is the newest publication in the Hesperia Supplement series, and it is a Heraklean undertaking: it publishes the full and final results of the Greek-American Excavations at Koutsongila, the eastern port of ancient Corinth. The scope and detail of the volume are extraordinary, as the publication meticulously documents the excavations, the artifacts, and the biological and human remains, all with thorough catalogues, rich illustrations, and discussion guided by methodology and a diachronic perspective. What the authors present, however, is not just a comprehensive artifact and burial assemblage but a nuanced social and religious history of the community at Kenchreai between the Early Roman and Early Byzantine periods. Rife, co-director of the excavations at Koutsongila and co-editor and contributor to Hesperia Supplement 52, discusses his experiences that led to this landmark publication and the lasting contribution he believes the volume will make to the field.

On the Edge of a Roman Port: Excavations at Koutsongila, Kenchreai, 2007–2014 (Hesperia Suppl. 52), edited by Elena Korka and Joseph L. Rife, is the newest publication in the Hesperia Supplement series, and it is a Heraklean undertaking: it publishes the full and final results of the Greek-American Excavations at Koutsongila, the eastern port of ancient Corinth. The scope and detail of the volume are extraordinary, as the publication meticulously documents the excavations, the artifacts, and the biological and human remains, all with thorough catalogues, rich illustrations, and discussion guided by methodology and a diachronic perspective. What the authors present, however, is not just a comprehensive artifact and burial assemblage but a nuanced social and religious history of the community at Kenchreai between the Early Roman and Early Byzantine periods. Rife, co-director of the excavations at Koutsongila and co-editor and contributor to Hesperia Supplement 52, discusses his experiences that led to this landmark publication and the lasting contribution he believes the volume will make to the field.

Beginnings

During the early to mid-1990s, when Rife was a student excavating at Isthmia and Corinth, he often swam at the beach on the site of the Roman harbor in modern Kechries. “I was always struck by the prominence—and mystery—of the coastal ridge that borders the ancient harbor front on the north, the Koutsongila Ridge,” he remembers. Soon, Kenchreai and the well-preserved remains of its cemeteries attracted his attention. But as an archaeologist and historian, his desire was to “investigate the provincial landscape beyond the centralized institutions and impressive buildings of major cities, focusing rather on questions of society, culture, economy, and religion across the full spectrum of urban and rural communities.”

He began working at the site in 2000, conducting survey, architectural study, and site conservation. He led the Kenchreai Cemetery Project from 2002 to 2006, with the support of the Ephorate of Antiquities in Ancient Corinth and the American School. Excavation on the periphery of the port town was the natural next step, and in 2007, he embarked on a joint campaign with Korka for three seasons of fieldwork (2007–2009). “Former ASCSA Director Jack Davis and his office showed great generosity and foresight in arranging the collaboration with Elena Korka as a joint Greek-American exploration of Koutsongila,” Rife recounts. “When we began digging in 2007, we possessed an extensive knowledge of the site drawn from previous fieldwork, as well as a clearly conceived and articulated set of objectives. On that basis we expected to find certain things, such as chamber tombs and cist graves, a cult site or temple complex, a locale of Early Christian worship, a residential quarter, and a boundary of some kind between the port town proper and its suburbs,” Rife explains.

Student team members excavating at Koutsongila, 2009 (Photo J. L. Rife)

The Excavations

What they found proved to be versions of their expectations, but the specific discoveries were entirely unforeseen: mosaic art as exquisite and skillful as any published from Corinth; a remarkable Octagon, likely a martyrium, a Christian holy site that must have been a well-known landmark and destination for visitors from far and wide; traces of pyre debris from a longstanding and massive operation to cremate the dead; and roadways that demonstrate how traffic moved between the northern suburbs and the harbor, traffic that likely included funerary processions.

One especially breathtaking find is the Silenus mosaic, which the team discovered in 2007. Rife recalls,

A young student was digging in the rough, sandy sediment at the bottom of a World War II turret. We were all disappointed that this artillery emplacement along the crest of the sea cliff, now mostly buried and overgrown, had turned out not to be the apse of an early mortuary chapel, as Tim Gregory had hypothesized decades ago. As the student wrapped up her unit, I encouraged her to dig down just one or two more centimeters, to level out the floor of the trench. We were both shocked when her handpick clicked against the intact mosaic pavement, and we quickly brushed off the bearded, enwreathed face in the emblema. In an amazing web of coincidence, the Germans who defended the ridge had unwittingly situated their turret directly over the mosaic; they preserved the mosaic by solidifying the cliff’s fragile edge with a heavy foundation; and we discovered the mosaic because we mistook the remains of the turret in the first place.

The Silenus mosaic graces the cover of the volume and is presented with stunning color illustrations in an entire chapter devoted to mosaic floors, including the elaborate mosaic floor in the Octagon and the mosaic debris from rooms in another building at the site. “The affluence reflected in the sophisticated art and architecture uncovered on the ridge points to the existence of a local elite,” Rife reflects, “who were presumably involved in the port’s commercial scene and who must have interacted with other leading citizens at Corinth and the Isthmus.”

The Silenus mosaic during excavation, with the turret still visible above it, 2007 (Photo J. L. Rife)

The many burials the team uncovered yielded abundant evidence for funerary ritual over time. “The discovery of small platforms associated with Late Antique graves reminds us of the importance of graveside offerings,” notes Rife, “while the predominance of simple pitchers, perhaps manufactured expressly for funerary use, points to the abiding significance of libations or communal drinking among Christian mourners.” Rife catalogues the burials in admirable detail, including plans for each grave with elevations, sections, and the locations of all human and artifactual remains. Photos document the burials during and after excavation, which provide readers access to the unique vantage point of the excavators as they worked. These burials are one of the richest contributions of the volume and demonstrate how much can be learned about the people of an area through funerary ritual. “The stark contrast between familial burial in chamber tombs during the Early to Middle Roman periods and familial burial in rock-cut or built cists during the Late Roman to Early Byzantine periods is a striking pattern,” explains Rife. “It reflects a broader paradigm shift in the mortuary practices of Greek society that is attested at numerous sites.”

Rife discusses skeletal remains with his students, 2008 (Photo J. L. Rife)

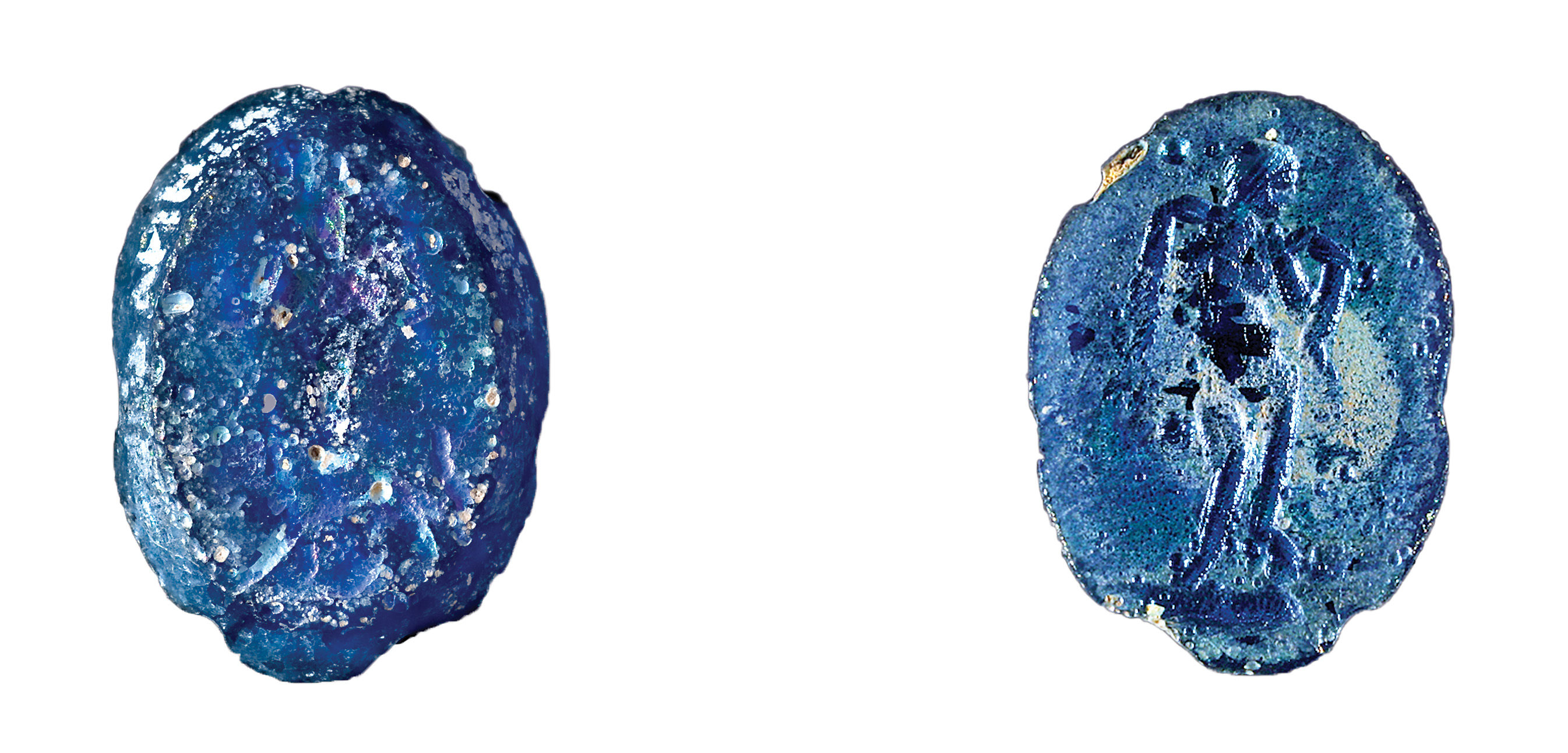

As for other memorable finds, “there are so many to choose from,” says Rife. “I think of the well-preserved floor deposit in tomb 7, full of Corinthian lamps, fine wares from Asia Minor, and a Pontic amphora, more or less where mourners left them in the first Roman centuries. I think of an Athenian lamp that imitates the North African style and bears remarkable imagery of Christ the Savior. I think of many aspects of the Octagon, such as the foundation and floor deposits, which together bracket the building’s construction and collapse.” There is also a stunning amount of notable glass, such as a possible Egyptian “kohl container” (a squat vessel that would have contained oils or perfumes), a molded purple-glass amphoriskos, and a personal amulet depicting Aphrodite and Osiris and invoking Jahweh. Equally important is the documentation of modern artifacts and debris scattered across the ridge, such as Italian and American bullet casings, and the careful recording of sardine cans and foil candy wrappers from World War II ditches.

Glass amulet depicting Aphrodite and Osiris (Photo D. Curtis)

The Study

“A complete publication of the excavations was our ultimate aim from the start,” admits Rife. “I admired the pioneering work of the American and British projects at Carthage in the 1970s and 1980s, and our team shared common ground with the concurrent project at Sikyon under the general direction of Yannis Lolos (the first results of which are published in Land of Sikyon [Hesperia Suppl. 39]).” This holistic approach to publishing archaeological data with its interpretive conclusions is, according to Rife, “good science and good cultural heritage management for today and tomorrow.”

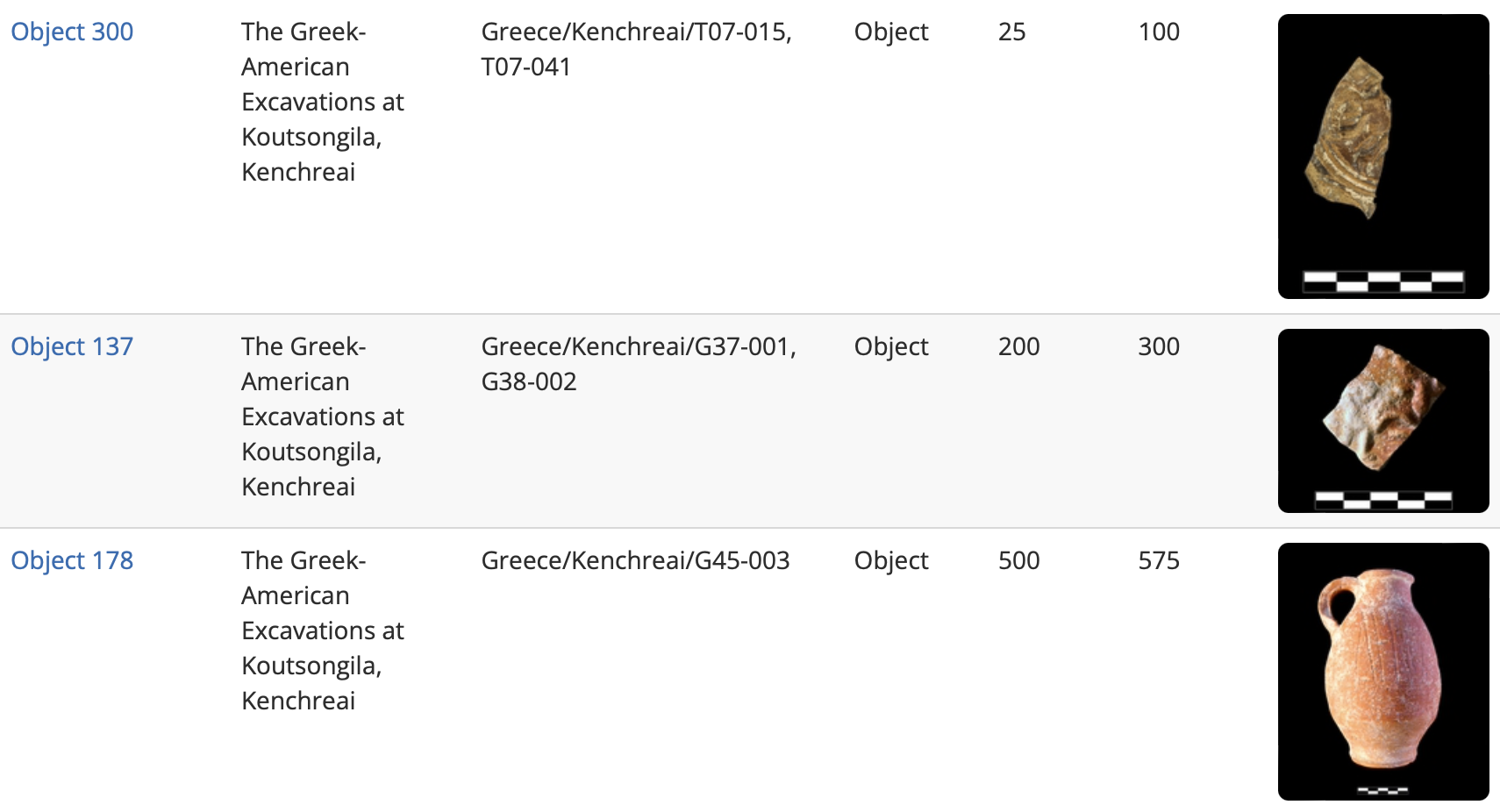

Koutsongila is a site endangered by clandestine digging and coastal erosion, and so preserving the archaeological record before it disappears became an urgent mission. Rife and his team wrote and edited their study within a decade of their final field season—a truly astounding feat considering the body of material. (The final page count for the publication is 1,376 pages, not including three digital supplements, which add another 148 pages!) This achievement attests to Rife’s commitment to making his evidence and conclusions accessible “to promote future research and popular interest, not to mention local identity formation.” It also serves as a model for how site directors and their teams can make their evidence available in a meaningful way, with lucid explanations of goals and techniques, and a narrative thread of recurring themes across the chapters; despite its scale, it is not a “sprawling data dump, or a confounding read at first sitting,” he observes. In this vein, Rife has made all of the data, including myriad color photos of inventoried objects, freely accessible through Open Context. “The full availability of our evidence allows researchers not only to test our conclusions but also to make their own, unrestricted by what we as authors define as useful or relevant.”

A view of the Koutsongila catalogue available through Open Context

With his experience working in Turkey, Italy, Tunisia, and Israel, Rife brings a more global perspective to his study at Koutsongila. “The ideologies and histories of archaeology vary significantly from place to place, even if the essential methodologies that researchers apply do not,” he notes. “I was especially impressed by the close interaction of my Greek colleagues and the government oversight of the excavations at Koutsongila, to the extent that it was the first foreign collaboration designed from the start with the three directorates of Antiquities, Conservation, and Reconstruction.” The members of the Greek-American team recognized the value of looking beyond the regional archaeological record and the traditional practices of Corinthian archaeology to map out a wider context and claim a richer perspective for understanding their site. Rife explains,

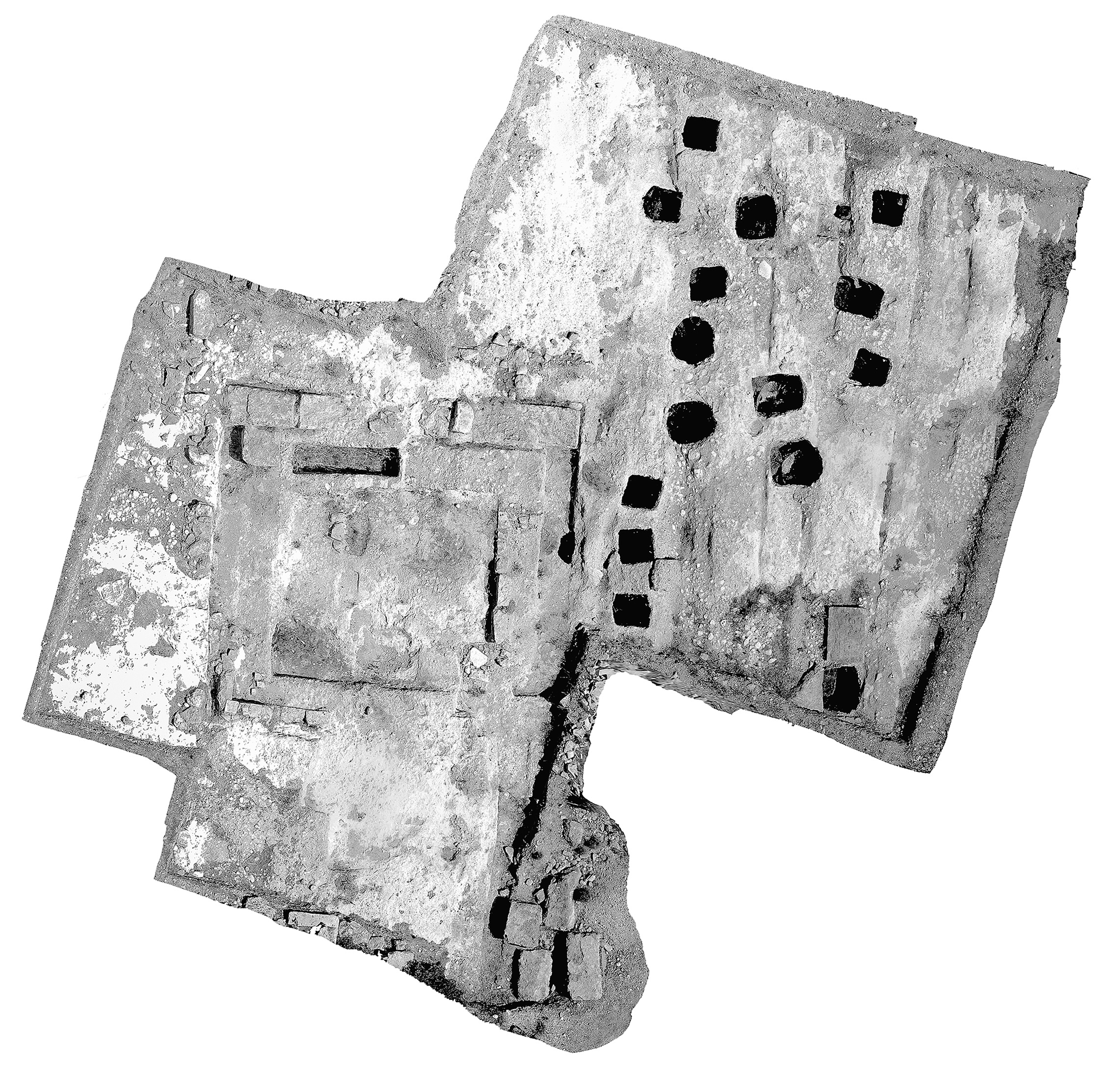

We found much to support the longstanding view that Kenchreai was more eastern and autonomous in character than the westward-facing Lechaion. The distributions of traded wares suggest regional zones defined by maritime commerce, from the Saronic seaboard to the urban center inland to the western Corinthia. While we document in detail the prevalence of pottery, lamps, glass, and decorative stone from Asia Minor, Syria-Palestine, and Egypt throughout the Roman era, we also find a noteworthy presence of western imports during all periods. Direct contact between coastal sites in the eastern Corinthia, such as the main harbor at Kenchreai and the zone of secondary landings and villas along the seashore to the north, finds evidence in the major cartroad that crossed the central slope of Koutsongila.

We are reminded how important it is to view any archaeological site in the region as a point within a network. The experiences, thoughts, and tastes of people in one place must have overlapped with those of people in another place; Corinthian religion as both a historical phenomenon and a collection of operating cults was multilocal; and communication and exchange between different places surely impacted economic, social, and cultural developments.

Aerial view of Building C1, showing the cartroad and graves, north at top (S. Copp)

There is much to be learned from the project, and not just academically. “While I faced the challenges of any excavation director, our team and its discoveries were so large and diverse that those challenges were magnified,” Rife relates. “Many might consider the logistical and administrative details to be mere curiosities, concerns such as getting buses, lunches, and portable toilets, renting storage space, and convincing deans and donors to support the work.” The project was a collaborative effort at all stages involving many people, as attested by the volume’s Appendix A, which gives a full roster of personnel for the excavations, representing many different backgrounds: students, researchers, professors, politicians, technicians, and local residents. This collaboration was “exhilarating and in the end hugely beneficial, even if, in the midst of it, to play with a metaphor, there were a lot of cooks—and sous-chefs and wait staff and valets—and a whole lot of broth—and bread and garnishes and beverages (I am glad the soup turned out as well as it did!).”

Rife directs a student team member on site, 2007 (Photo J. L. Rife)

The Study in Historical Context

As with many other sites in Greece, excavation and study at Kenchreai began in the early 20th century. The initial campaigns were undertaken in 1905 and 1906, and the American School continued exploration in the 1960s, with teams from the University of Chicago and Indiana University. The American expedition produced several publications, which, Rife reflects, “hold an admittedly odd place in the annals of Greek archaeology.” He explains that “the research team six decades ago struck out on its own path in the Corinthia: aside from Robert Scranton, the staff included many newcomers to the region, and they published their famous tomato-red volumes with Brill.” While the work by Scranton and his team may be dated and incomplete in various ways, it laid the groundwork for Rife’s own exploration of the area, making “several signal contributions to the field, including its exploration of littoral and marine environments, its analysis and conservation of glass, and its remote sensing and extensive survey around the harbor.” With no connection to Scranton’s team by personnel, licensing, or sponsorship, Rife and his team sought to carry on their work and “do right by a site of undeniable importance.” They aimed to broaden the understanding of Kenchreai in response to earlier excavations there, to find out what could be learned now—decades later—about the margins of the settlement. “Ultimately,” he notes, “we confirmed some of the theories our predecessors had advanced.”

Building from this earlier scholarly record seems to have only empowered Rife and his team to create a publication that is both comprehensive and innovative. There are many features to highlight, including the volume’s foregrounding of research questions and an explicit rationale for the progress of fieldwork, the consistent evaluation of formation processes in interpreting the archaeological record, the full yet accessible stratigraphic report, the planning for site preservation from the outset, the reporting on conservation, the global field of reference in studying the artifacts, the contextualization of all finds within depositional sequences, the integration of environmental and biological science (from geology to plants to animals to people), the commitment to high-quality illustrations, and the inclusion of modern remains, particularly the foray into the archaeology of World War II. All these strategies culminate in a unified and contextualized history of activity at Koutsongila across many periods.

Rife and Korka (center) with members of the Greek Archaeological Service (Photo J. L. Rife)

Readers are handed a lens into the lives of the people from the area, and this humanization of the material is impactful on many levels. “We endeavored,” Rife remarks, “to recover the ritual behaviors and social structures of people who inhabited a natural and built environment, and to trace their capacity for adaptation, their prosperity, and their interconnectivities over time. It is a study not just of the physical remains but, more importantly, of the community behind those remains—including the poor, the young, their animals, all of the local residents who have often remained invisible in past studies.” He adds, “we embraced peripherality as both an analytical category and an interpretive framework.” The concept of a place and a people “on the edge”—so aptly captured in the title of the volume—is interwoven throughout the publication; it connotes the ridge on the limit between the harbor and the hinterland, the passage between the spheres of the living and the dead, and the age of transformation at the end of antiquity. “While this focus draws our attention away from the central spaces and favored subjects that have long dominated our field,” Rife notes, “it demonstrates how much we can learn about a community at its margins and in its transitions.”

Future Endeavors

But Rife’s work at Kenchreai is not finished. With the publication of On the Edge of a Roman Port, there is now an opportunity for his team to revisit the earlier excavations conducted under Scranton. “We are systematically reviewing the finds from excavation during the 1960s in the harbor and reconstructing the depositional sequences at the north and south moles,” he reveals. Additional information on this project is available at http://www.kenchreai.org/.

He also leads excavations at Caesarea Maritima, on the northern coast of Israel. “The opportunity to work at two major harbors in the eastern Mediterranean has been an eye-opening experience for me, as I develop a new perspective on the life and landscape of port towns but also realize the close connections by maritime commerce between the Levant and southeastern Europe.”

On the Edge of a Roman Port: Excavations at Koutsongila, Kenchreai, 2007–2014 (Hesperia Suppl. 52) can be ordered from our distribution partners: Casemate Academic (in the United States) or Oxbow Books (outside of the United States).