A Wandering Copy Finds a Home: A 1559 Zurich Edition of Stobaeus at the Gennadius Library

The Gennadius Library has received an exceptional sixteenth-century printed book, generously donated by Maureen Rodgers, founder of the Rodgers Book Barn in Hillsdale, New York, and guided to the Library through the care of Patricia Marshall, retired Lecturer in Classics and Senior Associate of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. The book is a 1559 folio edition of John Stobaeus’ Sententiae, printed in Zurich (Tiguri).

Patricia sought a fitting “home” for what she aptly described as a “wanderer.” Its arrival at the Gennadius Library brings to rest a book whose long journey across centuries and borders is written into its very pages.

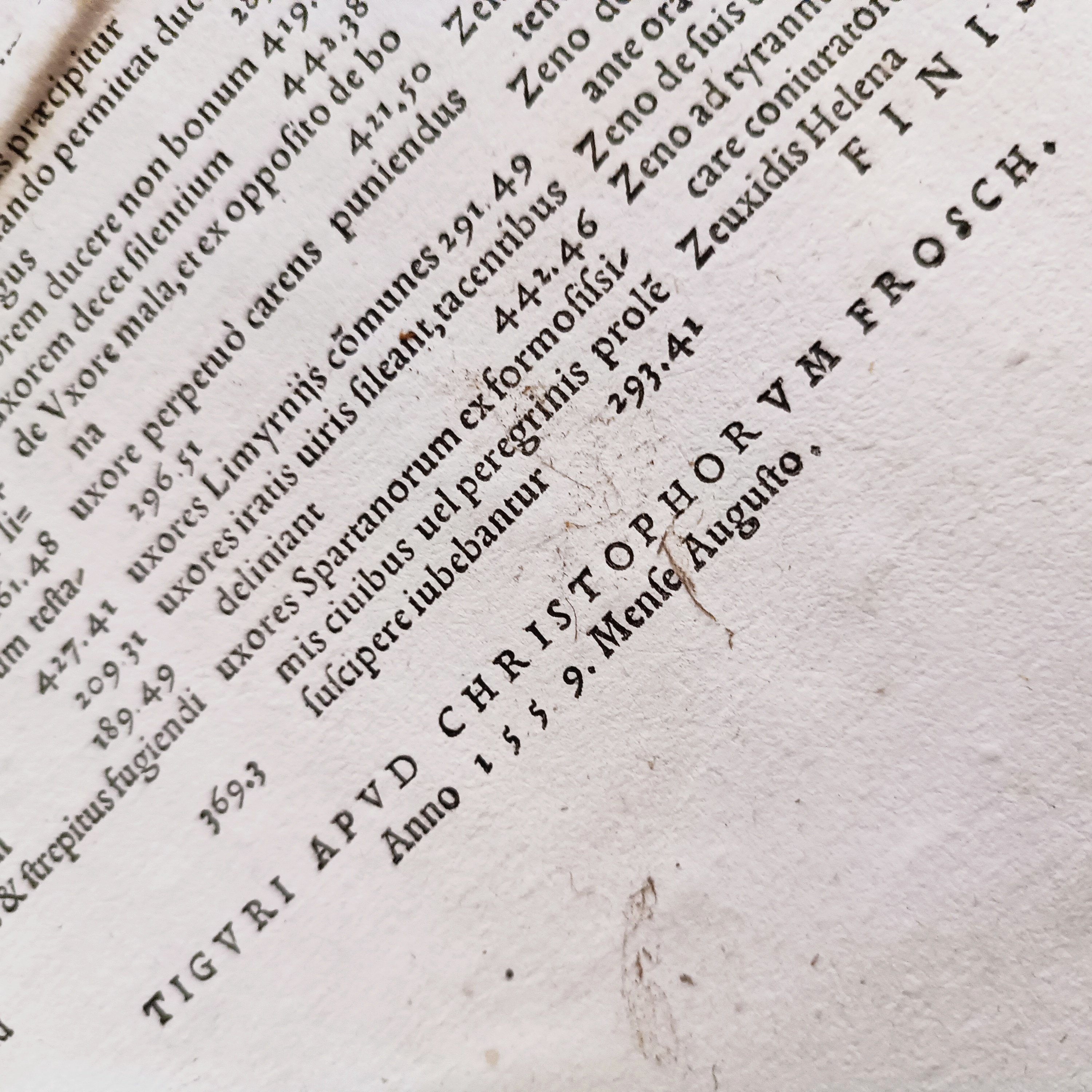

Printed by Christoph Froschauer, one of the most important printers of Reformation-era Zurich, the volume represents the tertia editio of the first part of Stobaeus’ Sententiae, known as the Eklogai. Stobaeus’ fifth-century anthology—drawing on approximately 250 ancient authors—was a cornerstone of Renaissance learning, offering access to Greek ethical, philosophical, and rhetorical thought at a time when direct engagement with classical sources was central to humanist education.

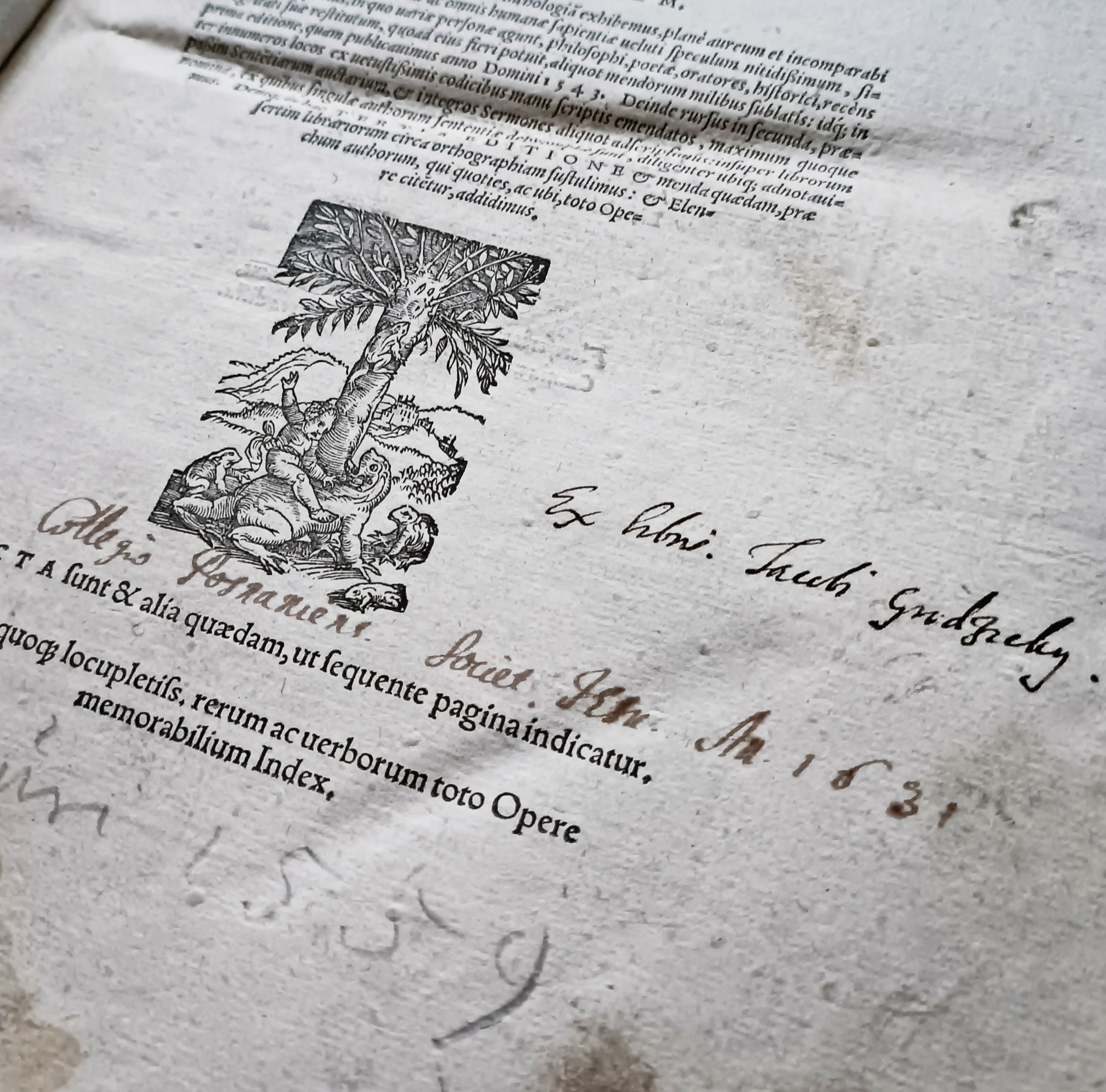

The text was edited and translated into Latin by Conrad Gessner, ensuring that the Greek original and its Latin rendering appear in parallel columns. The edition is of special scholarly importance. In the ad lectorem, (to the readers) the editor explains that this third edition revises and expands the editions of 1543 and 1549, introducing further corrections from authoritative manuscripts, adding new material, and improving accuracy throughout. Particular care is given to correcting errors and expanding the index of authors, thereby increasing the work’s usefulness and reliability. Armed with improved readings, Gessner returned to Zurich and produced this revised edition, enriched with additional material and a comprehensive index of notable subjects and words. The book thus stands as a testament to the dynamic nature of Renaissance philology, grounded in manuscript study, travel, and constant revision.

The physical book is equally striking. The copy is bound in brown leather binding over wooden boards (16th century), richly blind-tooled with framed panels and floral motifs. A handwritten title survives on the fore-edge, a common early shelving practice for identifying the volume. Despite minor watermarks along some page edges and the loss of its original metal clasps, the copy is in good overall condition. It retains fine typographical features and decorative initials designed by Hans Holbein the Younger, whose woodcut letters lend visual distinction to the text. As a material object, it embodies the ideals of sixteenth-century scholarly printing: clarity, authority, and elegance.

What really makes this copy stand out is the story written all over its pages. Handwritten notes on the title page name an early owner, “Iacobus (Jacob) Kudzicky,” and record the book as a gift to the Jesuit College in Poznań in 1631 (Donatus Collegio Posnaniensi Societatis Iesu Anno 1631). These brief inscriptions tell us that the volume became part of the college’s library, an institution founded in 1572 that was a major center of learning in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until the Jesuits were suppressed in 1773. Although we don’t know much about Kudzicky himself, the notes firmly place the book in an early modern academic setting.

The later handwritten additions make this picture even richer. Notes on pp. 244–245, written by scholarly hands in the sixteenth or seventeenth century, include ethical reflections inspired by Plato— grappling with the problem of good and evil—alongside what appears to be a list of errata from other readings, suggesting careful and critical reading. On pp. 496–497, a longer Latin piece reflects on the vanity and transience of earthly life, composed on the occasion of the death of a fellow student. Signed by Albertus Poniecki and Aemulus Kopraszewski, this text reads as a student exercise in rhetoric and moral philosophy. Taken together, these annotations turn the book into a lively record of teaching and learning, showing how classical texts were actively used in Jesuit education.

Now housed in the Gennadius Library, this well-traveled copy now takes its place alongside our 1536 Trincavelli and 1575 Canter editions of the Eklogai, neatly filling an important chronological and textual gap in the collection. Its journey—from Zurich to Poznań, then to the United States, and finally to Athens—echoes the circulation of books, ideas, and scholarly practices that the Gennadius Library is dedicated to preserving and sharing.

We are especially grateful to Dr. Stavros Grimanis for his meticulous palaeographic work on the handwritten ownership notes and scholarly annotations preserved in this volume.