A Book Twenty Years in the Making: Reflections from the Authors

A new ASCSA publication, coauthored by James C. Wright and Mary K. Dabney, presents the material of a Late Helladic settlement found on Tsoungiza, a hill dominating the Nemea Valley. The authors spoke with the American School about their new volume, The Mycenaean Settlement on Tsoungiza Hill (Nemea Valley Archaeological Project III) and shared some of their favorite experiences and memories from their work at the site.

While excavations by the ASCSA in the region began in 1892, it wasn’t until 1924 that Carl Blegen began digging trial trenches at the top of Tsoungiza Hill, which uncovered a large Neolithic refuse dump, as well as remains from the Early Bronze Age and later. Blegen soon turned his focus to new excavations at Zygouries and handed the Nemea Valley project off to James P. Harland, who continued with more extensive excavations in 1926 and 1927. But Harland never published his findings, and this would prove fortuitous for the future Nemea Valley Archaeological Project (NVAP).

Carl Blegen’s excavations at the southern end of Tsoungiza Hill, April 16, 1924 (J. P. Harland Archive)

After working with Steve and Stella Miller at the Sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea in 1974, Wright was approached by Steve in 1981 about tackling Harland’s unpublished prehistoric remains found on Tsoungiza. Dabney joined Wright for a pilot project that summer, and according to Wright, “out of that, the Nemea Valley Archaeological Project was born.” They conceived of it as an excavation and regional survey to explore the “cultural ecology” of the region. Their goal was an all-encompassing endeavor to understand how the “human occupation and exploitation of the valley changed under different economic settings over time, from as early as we could document up to the present day.”

A reconstruction of the West Building (© LearningSites; J. C. Wright and D. Sanders)

Wright and Dabney’s publication, The Mycenaean Settlement on Tsoungiza Hill, is the third volume in the NVAP series. The first volume, The Early Bronze Age Village on Tsoungiza Hill by Daniel J. Pullen, published the project’s excavations into Harland’s trenches on the top of the hill, which involved coordinating Harland’s notes and the actual remaining strata Harland uncovered with more recent stratigraphic observations. In contrast, NVAP III focuses on areas not touched by Harland, although Wright and Dabney were able to use exploratory soundings in Harland’s Trench L to locate Building K, enabling them to “place the large complex of buildings Harland found accurately on our topographic plan. Our excavation unit (EU) 10 excavated a dump of material of LH IIA that we believe came from the easternmost buildings of that complex.” The volume also features many important chapters from a large number of contributors. For example, Jeremy B. Rutter’s study of the MH III, LH I, and LH IIB pottery, Susan E. Allen’s analysis of the botanical remains, and Paul Halstead’s analysis of the faunal remains all contribute to a deeper understanding of the site and its surroundings. Wright and Dabney explain that “no other excavation yet published provides for all categories of finds such a richly, carefully, and systematically collected and analyzed set of data for almost every phase from MH III through to the very beginning of LH IIIC.” But as Wright admits, this unprecedented study had to wait a long time to become the important volume it is today:

This publication should have been finished twenty years ago. For various reasons many of us got caught up in other obligations. It took Mary Dabney’s leadership and firm insistence to gather all the manuscripts and illustrations, to undertake editing, and to insist on meeting deadlines to bring it all together. In some respects the extra time made the analyses richer because we all brought the experience of our mature years to the interpretation. But were it not for Mary, this study would never have been completed.

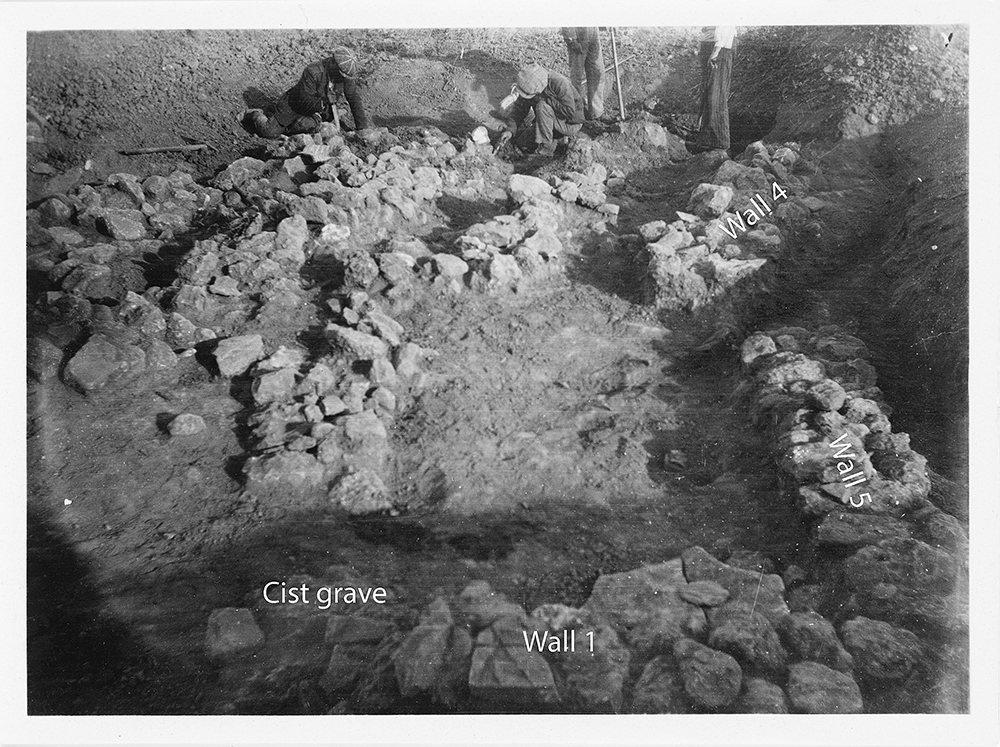

Harland’s excavations of Building K in the 1920s (J. P. Harland Archive)

The interdisciplinary nature of the work means that even though there are numerous interesting finds, the most important discovery for Wright and Dabney is the conclusions they were able to draw from the ample data they collected. They explain, “The most interesting discovery of Tsoungiza during the Mycenaean period is not any particular find but rather that our evidence suggests that the settlement and the valley seem to have been largely held as an independent or private landholding of the community, which voluntarily decided to participate in the economy that centered around ancient Mycenae when it rose to power.” For Wright, this is especially visible in the shifting mortuary practices as the community adopted the Mycenaean chamber tomb for family burials.

Restored vessels found at Tsoungiza on the floor of a room uncovered in excavation unit 7 (T. Dabney)

Throughout the excavations, the archaeological team continually felt the presence of the families that have lived in the area for generations. Many workers on the site in the 1980s lived adjacent to the excavations or had relatives—fathers, grandfathers, uncles, great uncles—who worked for Harland in the 1920s. The excavation team rented houses, borrowed tools, and sometimes purchased land from the locals, though such efforts weren’t always successful; they were unable to purchase or re-excavate the field where Harland’s Trench L was located, stopping them from checking Harland’s reported findings. But in other situations, the locals were a valuable asset to the excavations. George Papaioannou, the former mayor of Heraklion (Archaia Nemea) who owned land adjacent to the excavations, allowed the team free use of his chicken sheds and water to process finds. Perhaps most importantly, the excavation team interacted with the families on a social level: attending workers’ banquets, weddings, funerals, and local festivals. Wright and Dabney reminisced about their time at Tsoungiza: “We convinced one family to whitewash their family chapel of Ayia Paraskevi (St. Friday, the Day of Preparedness) and celebrate the eve of the saint’s day one summer with a slaughtered lamb, traditional music and dancing, and consumption of too much of the family’s household wine!” It was these experiences that make for some of Wright and Dabney’s favorite recollections of Tsoungiza. They explain that their strongest memories “are those that we share with the many students and many villagers we worked with—discoveries in the trenches and museum, meals we shared together at the dig house and in the homes of villagers, and the intellectual development of our students, many of whom have gone on to successful careers of their own.”

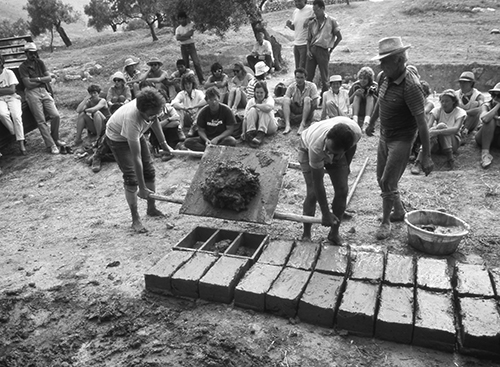

With guidance from the local residents, the NVAP team learned to make sun-dried mudbricks (T. Dabney)

Now that NVAP III has been published, Wright and Dabney are returning to Kommos. They became interested in the site when Joseph and Maria Shaw mentored them early in their careers. When Wright was director of the ASCSA, he helped the Shaws develop a site conservation plan for Kommos that was approved by the Ministry of Culture. He is now working with the Ephoreia to implement the plan with the hopes of opening the site to the public in the next several years. Both Wright and Dabney are looking forward to the end of the pandemic so that they can start working with conservators to stabilize the standing remains of the Bronze Age Mediterranean port.